Given the reverence for Hitchcock’s 1958 masterpiece today, people are often surprised to learn that on release, “Vertigo” was a bit of a dud, barely recouping its costs and generating only mixed reviews.

This tangled tale of murder and obsession may simply have been too twisted for Eisenhower-era audiences to accept.

The story also strained credulity for some viewers; after all, what are the chances of meeting your dead lover’s identical twin on the street, and convincing her to remake herself in the prior lady’s image?

Then there was the fact that this film, unlike any Hitchcock entry preceding it, featured a villain who appears to get away with his crime. This was highly unusual for any movie of the time.

Though the censors forced Hitch to shoot an alternate ending suggesting that the bad guy was about to be caught, he knew it would blunt the movie’s impact and successfully lobbied to exclude it.

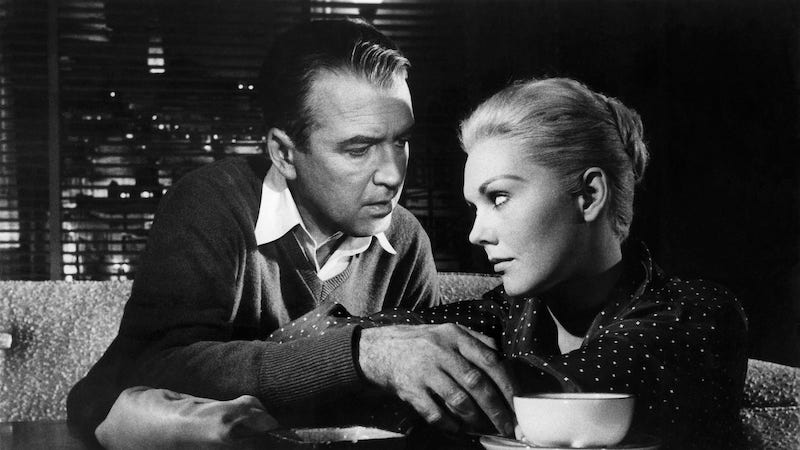

Hitchcock himself had a more straightforward explanation for the film’s disappointing reception: his star James Stewart was simply too old to play Scottie Ferguson, a man in the heat of sexual obsession. Stewart was then just about to turn 50, 25 years older than co-star Kim Novak.

On the face of it, he’d seemed like the right choice. A powerful actor and a major star, Stewart had a knack for dark, intense portrayals, on full display in his Anthony Mann westerns and, of course, in Frank Capra’s “It’s a Wonderful Life,” yet another classic that fizzled on first release.

Having worked three times before (on 1948’s “Rope,” 1954’s “Rear Window,” and 1956’s “The Man Who Knew Too Much”), the director and star welcomed a reunion. Still, after “Vertigo” the two would never work again, though Stewart had badly coveted the role of Roger Thornhill in “North by Northwest” that went to Cary Grant.

Due to rights issues, “Vertigo” was one of five Hitchcock pictures that went out of circulation for over two decades, and only became available again in the early ’80s , after the director’s death. The film would now be seen by a whole new generation, and their elders also got to view it with fresh eyes. Thus a critical re-assessment began.

The idea for “Vertigo” began with two French mystery writers who’d caught Hitchcock’s attention in the early fifties: Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac. They’d written a novel called “Les Diaboliques” that he wanted to adapt. However, their countryman Henri-Georges Clouzot snapped up the rights first and made the fabulous “Diabolique” (1955), starring Simone Signoret.

Undeterred, Hitch decided to adapt another of their books, “D’Entre Les Morts,” which translates to “From Among the Dead.” After rejecting two screenplay drafts from Maxwell Anderson and Alec Coppel, Hitch hired Samuel Taylor, who wrote the final script off the director’s own outline, without reading the prior two attempts.

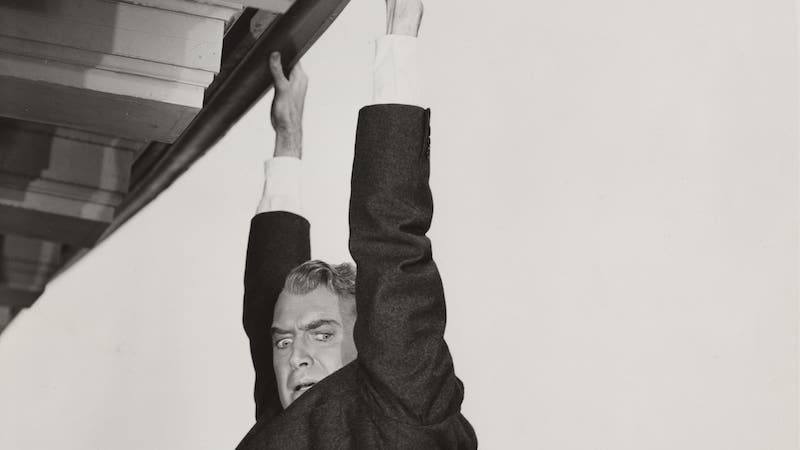

Scottie Ferguson is a police detective in San Francisco who almost falls off a roof while chasing a suspect, and as a result contracts a severe case of acrophobia (fear of heights) which in turn causes the extreme dizziness called vertigo.

Now retired from the force, Scottie hears from an old classmate who wants him to follow his young wife, not because he thinks she’s cheating on him but because she’s exhibiting odd behavior, often entering into trance-like states. He simply wants to know where she goes when she disappears for hours on end.

Ferguson agrees to take the assignment, and begins tracking the wife, a stunning blonde named Madeleine, all over scenic San Francisco. He eventually falls for this troubled lady, particularly after he rescues her during a suicide attempt.

Their relationship culminates in her (supposedly) accidental death falling from a bell tower, with Scottie on the scene but unable to save her due to his condition. Lost in a fog of grief and guilt, he then spots her double on the street and proceeds to make her over in his dead lover’s image.

As Hitchcock himself summarized it: “To put it plainly, the man wants to go to bed with a woman who is dead.”

The director’s choice for the lady in question was originally Vera Miles, who’d appeared in his prior film, “The Wrong Man,” opposite Henry Fonda. Unfortunately, Miles became pregnant and had to back out. (Hitch forgave her, casting her again as Janet Leigh’s sister in “Psycho”).

Securing Kim Novak’s participation involved Columbia Studios loaning her out to Paramount, in exchange for Stewart’s agreement to reteam with Novak for Columbia’s “Bell, Book and Candle” later that same year.

Though the gorgeous San Francisco locales are one of the film’s undeniable strengths, location shooting happened over just sixteen days. Hitchcock most always preferred shooting on a studio set, as it gave him complete control.

He found the San Juan Batista mission just outside the city where two of the film’s most dramatic scenes take place, including the climax. He had to add the mission’s tall bell tower in post-production via models and matte paintings.

To simulate Scottie’s vertigo, Hitchcock employed a new shot dubbed the “dolly zoom.” This involved zooming in the lens while simultaneously pulling the camera back. Using it cost about twenty thousand dollars for several seconds of screen time, but the effect was worth the expense.

Saul Bass’s animated credit sequence was another innovation, all circles and spirals suggesting disorientation and a departure from reality, further enhanced by Bernard Herrmann’s haunting, hypnotic score- perhaps his best.

So just how far has “Vertigo” come since its initial lukewarm response in 1958? A very long way.

The British Film Institute’s prestigious poll of best all-time films, conducted once a decade, provides a revealing barometer: “Vertigo” was first listed as the seventh greatest film in 1982, and then climbed to the fourth slot in ’92. Ten years later it moved up to second place, and in 2012, it finally became number one, displacing the venerable “Citizen Kane.”

The Master would undoubtedly be proud, if slightly astonished. Is “Vertigo” indeed the best movie ever made? I’m not so sure, but it may well be Hitchcock’s boldest work, exposing his own fetishistic impulses towards those unreachable blonde beauties that populate so many of films.

And that in itself makes “Vertigo” well worth the price of admission.