Any serious, discriminating film fan should know the work of Elia Kazan, a brilliant director of stage and screen who helped transform acting — and the movies themselves — in the mid-twentieth century.

Kazan, born to Greek parents in Istanbul, traveled with his parents to America at an early age. The immigrant’s sense of being an outsider would permeate his later work, as he delved into the lives of the poor and disaffected in contemporary society.

After college, he enrolled for two years at the Yale School of Drama, then ended up in New York City in the pit of the Depression, where he joined a small progressive acting troupe called the Group Theater, which presented plays dripping with social commentary. There he met Lee Strasberg, a brilliant director who, along with Kazan, would develop a naturalistic acting technique widely known as “the Method.”

Though Kazan started out as an actor, by the mid-thirties he was also directing Group Theater productions. His breakthrough came with 1942’s “The Skin of Our Teeth” by Thornton Wilder.

By 1945, he’d established his reputation enough to break into film. His first full-length production was “A Tree Grows In Brooklyn,” based on the best-selling book by Betty Smith. “Tree” tells of a poor, sensitive girl (Peggy Ann Garner) and her relationship with her bitter, driven mother (Dorothy McGuire) and kind but alcoholic father (James Dunn). Though not a box office hit, the film won strong critical reviews for its realism and touching performances.

Two years later, Kazan’s concern with social issues would lead him to make a then-groundbreaking film about the scourge of anti-Semitism: “Gentleman’s Agreement.” Gregory Peck plays a gentile journalist who takes on the revealing assignment of posing as a Jew to experience discrimination first-hand. The picture garnered eight Oscar nods, and won three, including Best Picture and Best Director for Kazan. It would be the first of five nominations for Kazan over the next fifteen years.

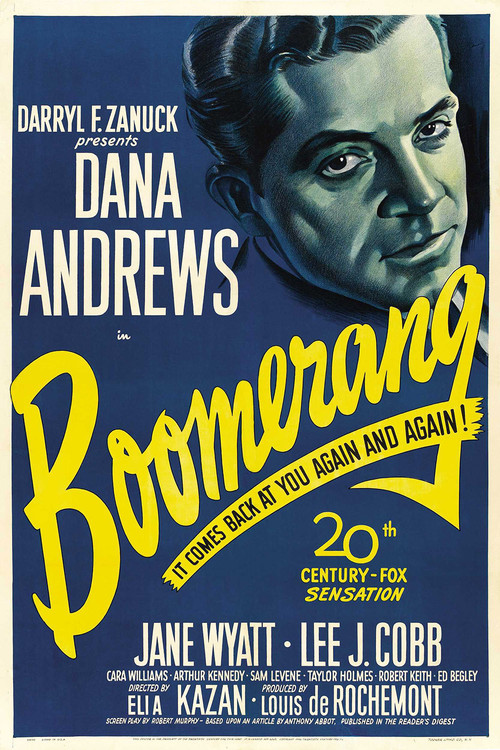

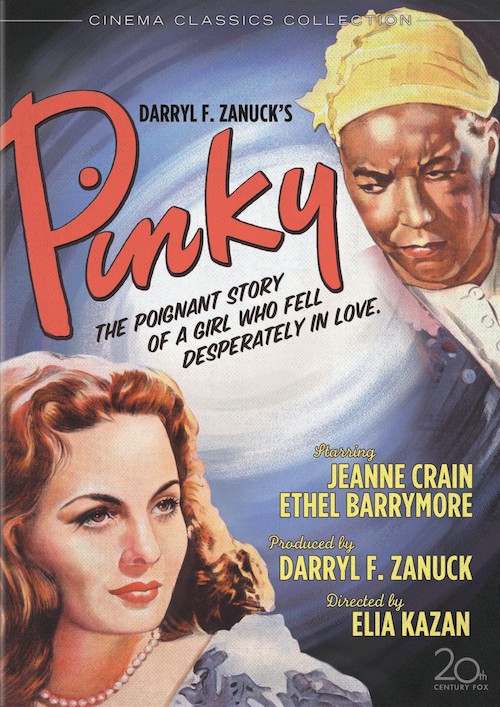

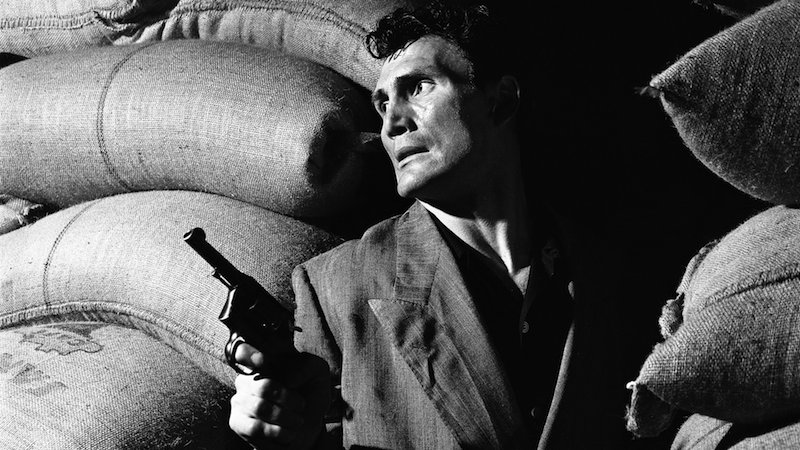

Kazan was now in demand and thriving in both stage and screen arenas: from 1947 through 1951, he’d direct the original productions of two enormously influential plays: Tennessee Williams’s “A Streetcar Named Desire” and Arthur Miller’s “Death Of A Salesman,” and also make the film version of “Streetcar,” along with “Pinky” (1949), another taboo-busting film about racism, and “Panic In The Streets” (1950), a manhunt film starring Richard Widmark and Jack Palance. Shot on location in New Orleans, it achieves the gritty immediacy of Italian neo-realism.

Then in 1952, just after shooting “Viva Zapata” with star Marlon Brando (whom he’d launched to fame in the stage and screen versions of “Streetcar”), the then rampant paranoia of McCarthyism finally caught up with him, and Kazan made a fateful choice. After first refusing to name names with HUAC (the House Un-American Activities Committee), he then decided to cooperate fully. Overnight, this prodigiously talented director became a pariah to many friends and associates. Kazan would never publicly regret or apologize for his actions, believing Communism to be a genuine threat to American ideals. This only hardened resentment against him.

Ironically, at this moment when he felt most shunned as a man, he became most inspired as an artist. He’d often muse on how the films he made after the HUAC incident were his most powerful — and most personal. A deep-seated, slow burning sense of defiance fueled his creativity.

His unquestionable masterpiece is 1954’s “On The Waterfront,” written by Budd Schulberg, and starring Brando in what would be his and Kazan’s third and final screen collaboration. Brando is Terry Malloy, a washed-up prizefighter who works for his brother Charlie (Rod Steiger). Charlie is second-in-command to gangster Johnny Friendly (Lee J. Cobb), who rules the waterfront through violence and intimidation. The film traces Terry’s evolution from cynical, apathetic punk to courageous crusader, who ends up informing on- and ultimately destroying- the Friendly machine.

“Waterfront” served as Kazan’s answer to those critical of his HUAC performance: the clear message is that speaking up against evil is a noble course. Regardless of whether this sways you in judging Kazan’s actions, it’s impossible to deny the impact of the film itself. The script is flawless, the acting superb, and the narrative immeasurably enhanced by Boris Kaufman’s stark cinematography and Leonard Bernstein’s moody, evocative score. The film would receive an astonishing 12 Oscar nominations, and win eight, including Best Picture, Actor (Brando), Actress (Eva Marie Saint), Writing, Cinematography, Editing, and another Best Director statuette for Kazan.

The director next took a chance on an unknown actor named James Dean in bringing John Steinbeck’s novel “East of Eden” to the screen. This time Kazan would shoot in widescreen and in lush, saturated color. Set in the wide-open California of 1917, the story updates the Cain and Abel tale to (relatively) modern times. The stern, religious, upstanding Adam Trask (Raymond Massey) has two sons, Aron (Richard Davalos) and Cal (Dean). Aron can do no wrong, while Cal’s incapable of doing anything right. Eventually a gentle young girl named Abra (Julie Harris) comes between the two brothers, but the bigger issue is whether Adam and Cal can ever heal their differences and make peace. This triumph garnered four Oscar nominations, including one for Kazan and Dean.

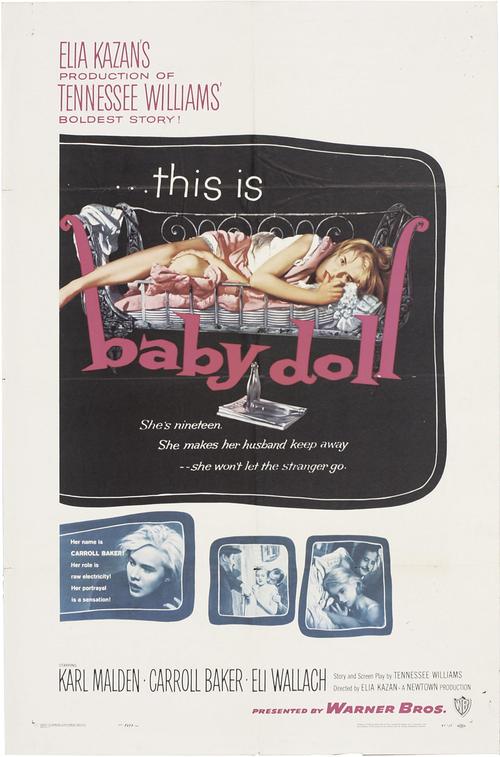

Kazan would make several more great films over the course of his thirty-plus year career, most notably “A Face In The Crowd” (1957) which introduced us to Andy Griffith, “Splendor In The Grass” (1961), which launched Warren Beatty, and “America, America” (1963), which traced his own uncle’s long, arduous voyage to the United States at the turn of the twentieth century.

By the mid-‘70s, a whole new generation of moviemaker had taken the reins in Hollywood, and Kazan quietly retired. Two decades later, as the now-frail director approached his 90th birthday, he was finally given an honorary Oscar for lifetime achievement, with the support of Karl Malden, Martin Scorsese, and Gregory Peck, among others. Though some in the audience, remembering his stand in 1952, refused to join in the applause, many others rose to their feet in appreciation of his outstanding body of work.

In accepting, Kazan said simply: “I want to thank the Academy for its courage, its generosity. Thank you all very much. Now I can just slip away.” And four years later he did, at age 94.

As the man who discovered and nurtured the likes of Brando, Dean and Beatty, Kazan would have loved to be remembered as an actor’s director. After all, he’d started out as one himself. He understood actors, valued them, and knew how bring out the best they had to give.

But ultimately he was more than that: a gifted, deeply emotional and intuitive storyteller who understood how to shape human drama into its most potent and moving form. For that, our eternal thanks, Elia Kazan.

More: On the Set of “Rebel Without a Cause” with James Dean and Nicholas Ray