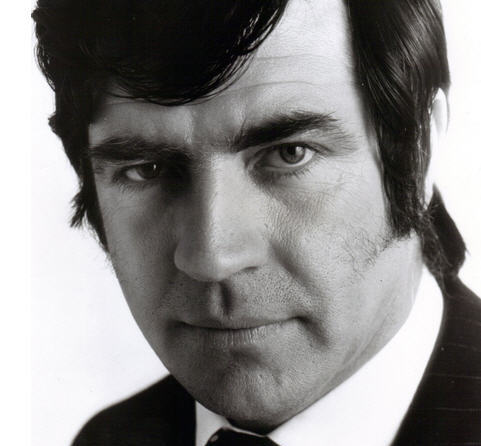

I have always been a huge fan of the late Alan Bates. His profound talent made him a joy to watch in most anything. Still, I’ve often wondered, why wasn’t he a bigger star? Eventually, I learned it was a matter of choice. He simply preferred to be a working actor.

He was born in Derbyshire, England in early 1934, the eldest of three sons. His parents were both talented amateur musicians who introduced Alan early on to the joys of performing. But rather than take up an instrument, Alan fell in love with acting, recognizing his life calling at the tender age of 11.

Later in life, Bates would turn to friends and, his green eyes flashing, utter his favorite axiom: “You’ve got to be driven!” He’d observed his father shrink away from becoming a professional cellist and take an insurance job to be closer to home. He would be different.

Excelling at his training and always pushing himself forward, he secured a scholarship to the prestigious Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts (RADA) in his late teens. There he’d study alongside the likes of Albert Finney and Peter O’Toole.

After a two year stint of compulsory military service, Alan joined the new English Stage Company, where in 1956, he made his West End debut in a play that would change the face of theater: John Osborne’s “Look Back in Anger.”

At age 22, Bates became a recognized actor, and over his career, would always feel at home in this gritter modern theatre that Osborne helped pioneer, soon to be expanded by such names as Harold Pinter, David Storey, and Simon Gray.

In 1960, Alan made his film debut in Tony Richardson’s “The Entertainer,” which Osborne wrote specifically for Laurence Olivier. The great actor delivered an astonishing change of pace playing Archie Rice, a musical hall entertainer in the provinces who’s gone to seed. Alan and Albert Finney, also in his first film, portrayed his two sons.

Over the following decade, Bates stayed busy, alternating between stage, film and television work. Maddeningly, two of his best early films are simply unavailable: Bryan Forbes’s “Whistle Down the Wind” (1961), and John Schlesinger’s “A Kind of Loving” (1962).

Though darkly handsome with a rich, mellifluous voice and arresting screen presence, he wasn’t primarily concerned with winning leading man roles. From the start, he was drawn to interesting character parts that challenged him.

Though darkly handsome with a rich, mellifluous voice and arresting screen presence, he wasn’t primarily concerned with winning leading man roles. From the start, he was drawn to interesting character parts that challenged him.

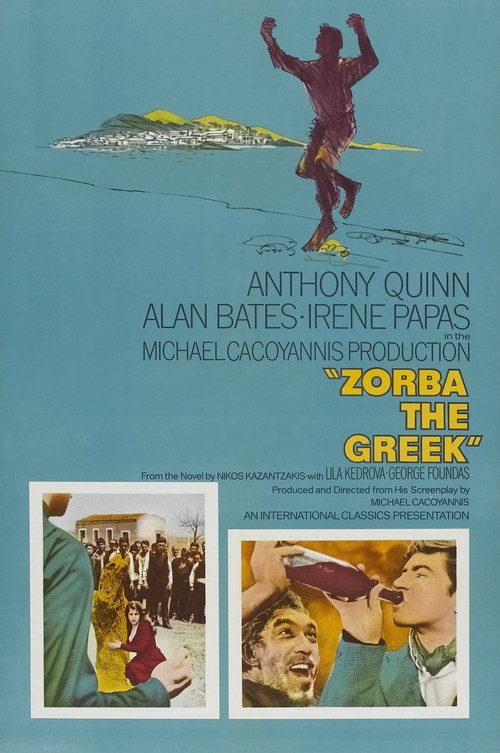

In 1964’s “Zorba the Greek” (1964), he plays a priggish young Brit to Anthony Quinn’s wildly emotional peasant, and in the popular comedy “Georgy Girl” (1966), he’s just one-third of a love triangle with Lynn Redgrave and Charlotte Rampling. In Schlesinger’s adaptation of “Far from the Madding Crowd” (1967), he plays a stolid farmer, one of three suitors seeking the hand of Julie Christie, with Terence Stamp in the plum role of a sexy, swashbuckling military man.

Bates was one of those rare professionals who truly believed that acting was a team sport. He loved being part of an ensemble. Rather than compete for the most camera time, he went out of his way to guide and encourage his fellow players.

In an industry filled to overflowing with outsize egos, Alan had very little “temperament.” Thus most every director, actor and writer in Britain wanted to work with him.

The one complaint about him was that he often found it difficult to make up his mind. Producers would tear their hair out getting him to commit to something, but once he did, he was all in.

Alan’s personal life was more complicated. Throughout his adult life, he was firmly closeted as a gay man. He had a string of male lovers over four decades, but still couldn’t affirm his homosexuality. He’d astonish his latest boyfriend by saying with a straight face, “I’m not gay, you know.”

This did not prevent him from accepting gay roles. Case in point: the most notorious scene in Ken Russell’s “Women In Love” (1969), based on D.H. Lawrence’s book, has his character wrestling in the nude with co-star Oliver Reed.

Off-screen, Bates was terrified of being outed and so remained highly discreet and protective of his private life. He was also drawn to many women, though, for the most part, only platonically. Still, he loved the idea of having a family, since he’d always remained close to his own parents (particularly his mother) and brothers.

Off-screen, Bates was terrified of being outed and so remained highly discreet and protective of his private life. He was also drawn to many women, though, for the most part, only platonically. Still, he loved the idea of having a family, since he’d always remained close to his own parents (particularly his mother) and brothers.

Enter Victoria Ward, a sometime model, actress and poet, whose emotional vulnerability appealed to the caregiver in Alan. She had been orphaned as a child, and her fierce beauty and intelligence belied an essential fragility. When Vicky got pregnant by him in early 1970, they decided to marry. Twin sons, Tristan and Benedick, were born later the following year.

Thus began a disastrous union that would eventually end in tragedy. Almost from the start, Vicky showed signs of mental instability and an eating disorder which only grew worse. She simply wasn’t equipped to be a mother. Since she firmly believed soap and most food contained harmful chemicals, the twins grew up often dirty and malnourished.

Meanwhile, Alan was off working, supporting the family. He knew there were serious issues, but his absence prevented him from seeing the full picture. Perhaps he suppressed the truth because he didn’t want to face doing something about it. It would be too painful, too public.

He was also unable to keep away from men for very long. Bates coped with all this personal turmoil by working, working, working. And he did some very fine work indeed.

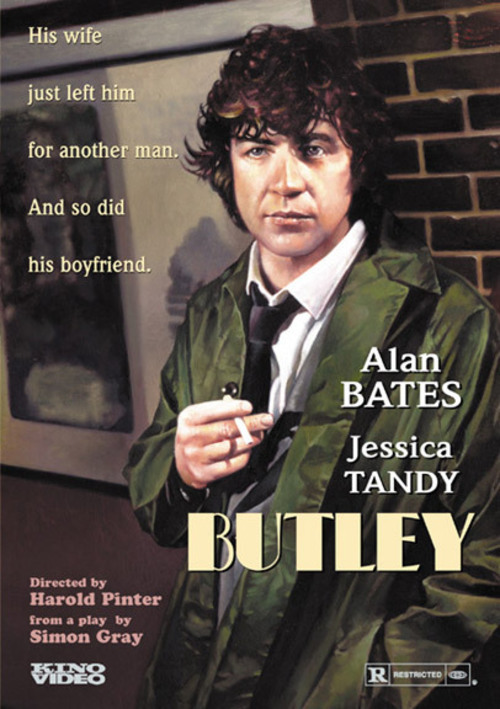

One of his best stage roles from this time finally made it to the screen in 1974: Simon Gray’s “Butley,” with Bates scoring as a bitter, dissolute teacher whose life is coming apart. Many have claimed this was the perfect marriage of actor and writer.

Alan had already received a Best Actor Oscar nod for 1968’s “The Fixer,” but had never been drawn to Hollywood nor established himself as big, bankable name in America. This had been a conscious choice.

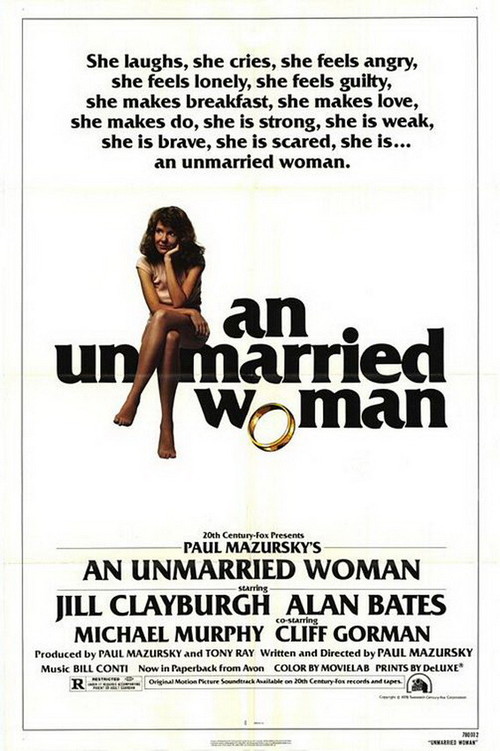

In 1978, director Paul Mazursky approached him to appear in his next film, “An Unmarried Woman,” about a wife (Jill Clayburgh) forced to rebuild her life after her husband (Michael Murphy) leaves her for a younger woman. Bates would play Saul Kaplan, a witty, scruffy painter who brings hope and romance back into this bereft lady’s life.

Alan flew Vicky and the twins over to the States for the duration of shooting. The resulting film was a hit, earning three Oscar nominations. He then seriously debated building on this success and re-settling in Hollywood. The parts were there, the weather was fabulous, and the money plentiful. Ultimately though, he realized that he missed England too much to stay.

The years to come were marked by much the same pattern: Alan working continually on stage, in film and TV — and loving it. Sadly, over this time Victoria’s mental condition further deteriorated. She and Bates had long separated, but eventually, he had to remove his sons from their mother’s care. It was all becoming unbearable, and potentially dangerous.

The years to come were marked by much the same pattern: Alan working continually on stage, in film and TV — and loving it. Sadly, over this time Victoria’s mental condition further deteriorated. She and Bates had long separated, but eventually, he had to remove his sons from their mother’s care. It was all becoming unbearable, and potentially dangerous.

As of 1990, Tristan and Benedick had miraculously survived and grown into tall, handsome young men. Both were looking towards acting careers. But Tristan had a wild streak, and on a visit to Japan, accidentally overdosed on heroin. He was just 19. Two years later, his mother Victoria finally succumbed to anorexia.

These double tragedies affected Alan deeply. Beyond the grief, there was guilt about his past avoidance of the issues at home and his too frequent absences. Drawing closer to surviving son Ben, he kept doing what made him whole: acting, while also relying on the companionship of close friends like actress Joanna Pettet, whom he’d first met in a stage production back in 1964.

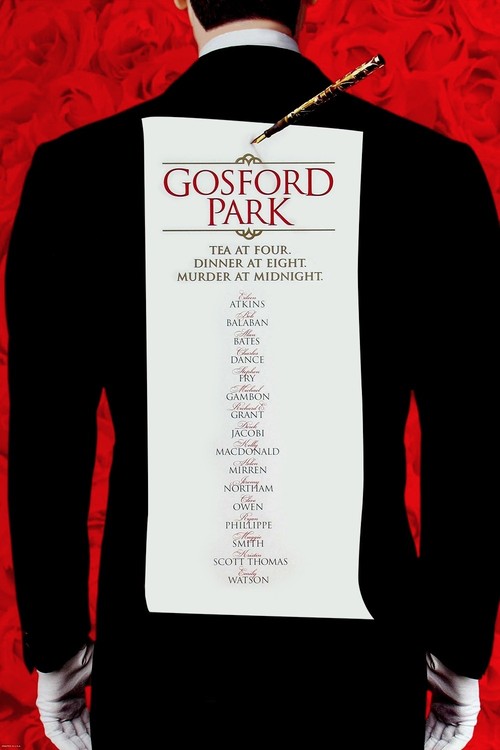

Two years after appearing as the butler Jennings in Robert Altman’s “Gosford Park,” Alan Bates learned he had pancreatic cancer, with just months to live. He had finally received a knighthood, having been appointed a CBE (Commander of the British Empire) in 1996.

The outpouring of love and regard for Alan Bates leading up to and following his death in late 2003 was astonishing, but not surprising. With all he’d faced and done, it was hard not to adore Alan, for his wit, kindness, and generosity to all lucky enough to have known him.

We his public feel much the same way. Farewell and thanks to Sir Alan Bates.