Westerns seem like an endangered species these days. With the studios depending more and more on international distribution and formula entertainment that can cross borders, the verdict is that the Western just doesn’t travel well.

In the past, here and abroad, the western film genre always struck a special chord because it signified the building of America, evoking the tough pioneering spirit of our first settlers, adventurers and explorers trekking into unfamiliar, dangerous territories. Whatever dramatic liberties may be taken, these movies show that the exertions of these intrepid souls did as much to link the Atlantic and the Pacific as did the expansion of the railroad.

The western crusade is as integral to our film traditions as to the building of our country, tracing back to “The Great Train Robbery” in 1903, and extending through the silent serials of our first cowboy star, William S. Hart. With few exceptions, Westerns would then become a staple of those “B” features that would always precede the main event at the local cinema.

A former USC football player named Marion Morrison would toil in these “oaters” during this period, until an older, sometime friend and mentor named John Ford gave him a chance at real stardom. By this time, Morrison had changed his name to John Wayne. Director Ford’s movie was called “Stagecoach” (1939), and it would prove to Hollywood that the Western form did not deserve to be confined to serials and “B” pictures.

“Stagecoach” endures as much for its script and characters as for its rousing Indian battles. The film focuses on a varied group of travelers who embark on a perilous stagecoach journey through hostile Indian territory. Passengers include Dallas (Claire Trevor), a music-hall performer, an alcoholic doctor (Thomas Mitchell), a wily gambler (John Carradine), and a wanted outlaw known as the Ringo Kid (Wayne). Shot in Monument Valley, Utah, Ford’s favorite western locale, the quality and impact of this picture proved once and for all that westerns need not be the province of second-rate studios and “B” serials, but the stuff of “A” features, made and released by major studios, and reflecting meaningful human drama.

Soon legendary director William Wellman would demonstrate this again with “The Ox-Bow Incident” (1943). Here, a well respected rancher is murdered, and his cattle stolen. A horde of outraged townspeople, hungry for swift frontier justice, prevail over calmer and wiser souls, assemble a posse, then find and hang three men they believe to be guilty. But are they? This tense, hard-hitting classic, not quite 80 minutes in length, exposes the ignorance and tragedy of mob justice, and its themes still feel relevant today. Henry Fonda is superb as an unwilling, dissenting witness to the event, and both Dana Andrews and a young Anthony Quinn are compelling as two of the condemned men.

Just three years later, Fonda would team with director John Ford in the definitive version of the fabled gunfight at the OK Corral, “My Darling Clementine.” The story: former lawman Wyatt Earp and his brothers, moving their cattle near the town of Tombstone, are victimized by the Clanton gang, who steal their herd, killing youngest brother James in the process. Wyatt (Fonda) decides to stick around Tombstone with his remaining two siblings to solve the crime. He finds an unlikely ally in the ailing Doc Holliday (Victor Mature), a former medical doctor from back east who now unofficially runs the town. This near-masterpiece is consistently engrossing, boasting magnificent black and white photography. But that climactic scene where the Earps and Holliday finally confront the Clantons (led by father Walter Brennan) at the OK Corral is deservedly the stuff of movie legend.

Director Howard Hawks gave western icon John Wayne another indelible role in his masterful “Red River” (1948). He plays Tom Dunson, a bitter, unyielding cattle breeder forced to take his large herd through treacherous territory to save his business. His adopted son Matthew (Montgomery Clift) joins him, but when the two men lock horns over Dunston’s obsessive behavior and cruel treatment of his men, the older man expels his ward. Populated by a host of colorful supporting characters, including (again) Walter Brennan, “River” combines psychological drama, action and suspense in a stirring, expansive western landscape. The final settling of scores between Wayne and Clift is unforgettable.

James Stewart’s collaboration with director Anthony Mann in a series of westerns helped resuscitate the folksy star’s flagging career in the fifties, and introduced a darker, intriguing cast to his image. The first and best of these pictures is “Winchester ‘73” (1950), co-starring a young and slim Shelley Winters. Stewart is Lin McAdam, a vengeful man pursuing his father’s killer. In a shooting contest overseen by Wyatt Earp (this time played by Will Geer), McAdam wins the fabled Winchester ’73 repeating rifle, but is ambushed by a sore loser who steals it for himself. The rest of the picture ingeniously blends McAdam’s ongoing quest with the various characters who lay their hands on that rifle, notably a corrupt Indian trader (John McIntyre) and an unhinged gunman (Dan Duryea, in a hilarious turn). “Winchester” is tight, trim, and smart, and Stewart is magnetic as the driven hero.

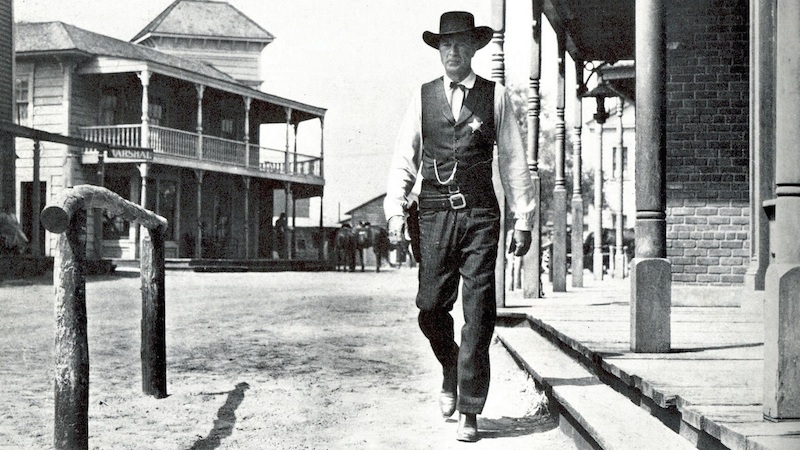

Gary Cooper was no stranger to westerns when he made the classic “High Noon” (1952) fairly late in his career. Like Wayne, he’d started in the business as an extra in westerns, and like Fonda, he had a laconic, uniquely American quality that suited him to the genre. “High Noon” tells of retiring Sheriff Will Kane, set to marry a beautiful, peace-loving Quaker woman (Grace Kelly) and begin a new life, only to learn that a vicious band of killers he’d sent to prison are coming back to take their revenge on him. While the easy course (a dignified exit) is clear, Kane chooses to stay, risking his future happiness to preserve the law-abiding principles he has fought for all his life. Starkly shot and directed by Fred Zinnemann, “Noon” is a spellbinding movie about what it means-and what it takes-to truly go it alone. Justly famous, “High Noon” is worthy of repeat viewings, and appropriate for older children.

Another indelible Western, made the following year, also bears revisiting: George Stevens’s “Shane.” A mysterious rider (Alan Ladd) arrives at a small farm occupied by Joe Starrett (Van Heflin) and his family- wife Marian (Jean Arthur) and son Joey (Brandon De Wilde). Shane offers to help work Joe’s land in exchange for temporary room and board. Little does Shane know he’s stepping into a hornet’s nest, with Joe soon pitted against a ruthless gang who want his fertile land for their cattle. Ultimately, Shane must put on the six-gun he’d foresworn using again to help Joe defend himself against a killer (Jack Palance) hired by the cattle interests. “Shane” is a mythic tale, beautifully realized on film. And be sure to catch that sublime, tear-inducing finale.

My final pick brings us back to John Ford and John Wayne, who ended up doing an astonishing 21 films together over the years. Perhaps their finest Western was released in 1956: “The Searchers.” The Duke plays Ethan Edwards, who returns to his frontier home after the Civil War hoping to resume a quiet life. Tragedy strikes when a local Indian tribe attacks his family farm, brutally murders Ethan’s brother and sister-in-law, and carts off their young daughter Debbie. Ethan and his adopted nephew Martin (Jeffrey Hunter) immediately saddle up to find her, with no idea that the journey will last seven years. Monument Valley in vivid color never looked more breathtaking, and Wayne scores as the obsessed, enigmatic Ethan. This gut-twisting, high-lonesome tale only grows more nuanced with each viewing.

Watch these movies and be reassured: the Western will never die.

More:

How Spaghetti Westerns First Got Cooked Up