Joel McCrea was always clear-eyed about his place in the Hollywood firmament. He once said that he got offered the comedies that Cary Grant passed on, and the westerns Gary Cooper rejected. Still, in the thirties and early forties, he managed to star in some bona fide classics across several genres.

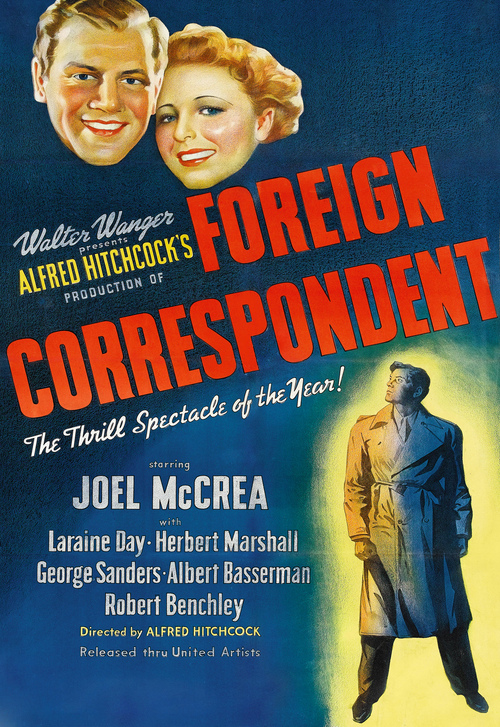

He was a favorite of comedy director Preston Sturges, playing the lead in two of his best films: 1941’s “Sullivan’s Travels” and 1942’s “The Palm Beach Story”. He also distinguished himself in some serious dramas and starred in the criminally underrated Hitchcock entry, “Foreign Correspondent” (1940).

Tall, handsome, and laconic, like his contemporary Cooper he epitomized the All-American male. The characters he played reflected traditional values of self-reliance, decency, and fair play. They were authentic, grounded types, graced with humility and an understated charm.

And this is just how McCrea wanted it. What few knew about him was that behind his folksy exterior lay an impressive shrewdness. He consciously wanted to cultivate a certain image, and would not stray from it. His goal was to play characters he could relate to, mostly in uplifting films. He was deliberate and strategic in his choices, and over a five-decade career, it served him well.

Joel McCrea was born in South Pasadena, California in 1905, the son of a utility executive. His family moved to Los Angeles when he was nine, just as the movie industry was exploding there. He attended Pomona College, and showed an early aptitude for acting, performing at the Pasadena Playhouse. He then started as an extra in films. Highly skilled on horseback, he was frequently hired as a stunt performer in Westerns.

At the tender age of 23, he was signed to a contract at MGM and cast in 1929’s “The Jazz Age,” starring Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. After one more picture there, he moved over to RKO, where his career started to take off.

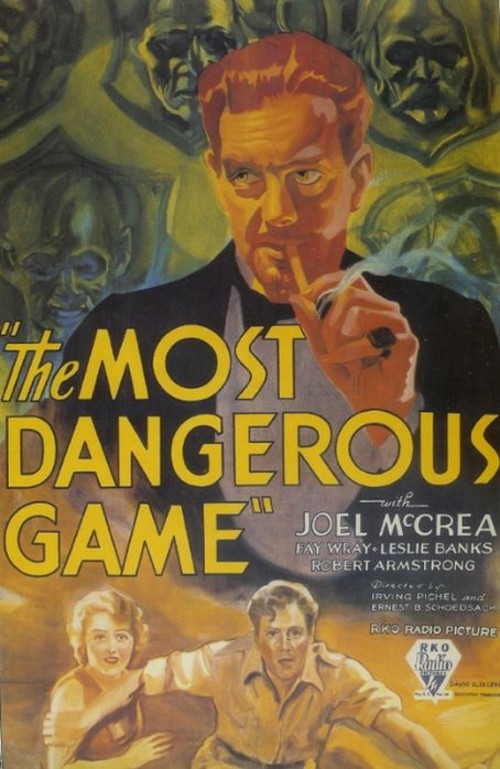

His most memorable effort from those early years was “The Most Dangerous Game” (1932), about a remote island where humans are hunted for sport. The film was made by the same team that within months produced the first “King Kong.” It used some of the same jungle locations and featured two “Kong” stars: Fay Wray and Robert Armstrong.

Right around this time, Joel set his sights on a beautiful young actress named Frances Dee, who was making the rounds in Hollywood. Reportedly, sometime in 1931 his car had pulled up to hers at a red light, and McCrea had looked over and doffed his hat to her. The very proper Frances considered this “forward” as they’d not been formally introduced. Turning up her nose, she stepped on the gas when the light turned green, leaving the young actor in the dust, literally and figuratively.

If this amusing incident is true, it hardly deterred him. In 1933, Joel was slated to star opposite Irene Dunne in John Cromwell’s “The Silver Cord” and lobbied hard for Frances to get a featured role. She did, and once the film wrapped, a whirlwind romance ensued. The couple wed in October of that year.

They would quickly have two sons, Jody and Peter, and then separate briefly in 1935. Once reconciled, they managed to stay together 57 years, adding one more son, David, to their brood in 1955. They also made several more pictures together, notably Frank Lloyd’s “Wells Fargo” (1937) and Alfred E. Green’s “Four Faces West” (1948), both Westerns. (McCrea wisely encouraged Frances to keep acting, reasoning that if he asked her to quit she might resent him for it later).

Over the following decade, Joel would make over thirty films, including William Wyler’s “These Three” (1936) and “Dead End” (1937), where he took top billing over Humphrey Bogart, at that time still relegated to playing heavies. He originated the role of Dr. Kildare in 1937’s “Internes Can’t Take Money,” was paired with frequent co-star Barbara Stanwyck in Cecil B. DeMille’s “Union Pacific (1939), and did his last great comedy in 1943, starring in George Stevens’ “The More, the Merrier” opposite Jean Arthur and Charles Coburn.

McCrea turned forty just as the war ended in 1945 and decided he wanted to focus on Westerns. As he explained it years later: “I liked doing comedies, but as I got older I was better suited to do Westerns. Because I think it becomes unattractive for an older fellow trying to look young, falling in love with attractive girls … I always felt so much more comfortable in the Western. The minute I got a horse and a hat and a pair of boots on, I felt easier. I didn’t feel like I was an actor anymore. I felt like I was the guy out there doing it.”

Joel could afford to make this choice, as by this time he’d become independently wealthy through his real estate holdings. He owed much of his good fortune to his old friend Will Rogers, who’d taken a shine to the young actor fifteen years earlier.

At one point, he’d counseled Joel to save half of what he earned and invest in land. The famously plainspoken Rogers put it this way: “You’re not worth nearly as much with a big house, a big car and no land.” McCrea took his advice and ended up owning a ranch of three thousand acres in what is now Thousand Oaks, California. He later confided that he’d made much more money in real estate than movies.

In fact, on his IRS form Joel listed his profession as “rancher” and his hobby as “acting.” When a couple of IRS agents came to check out his story, Joel showed them the calluses on his hands and said, “I didn’t get those on a Hollywood set.” The agents departed, satisfied.

Between 1946 and 1960, McCrea made about thirty Westerns, and in a sense his dual identities as rancher and actor almost merged. In the early fifties, he performed in a Western radio series called “Tales of the Texas Rangers.” Then in 1959, Joel co-starred with son Jody in “Wichita Town”, a TV series that lasted just one season. (Jody, who died in 2009, was best remembered for a recurring role in a series of Frankie Avalon/Annette Funicello “beach” pictures.)

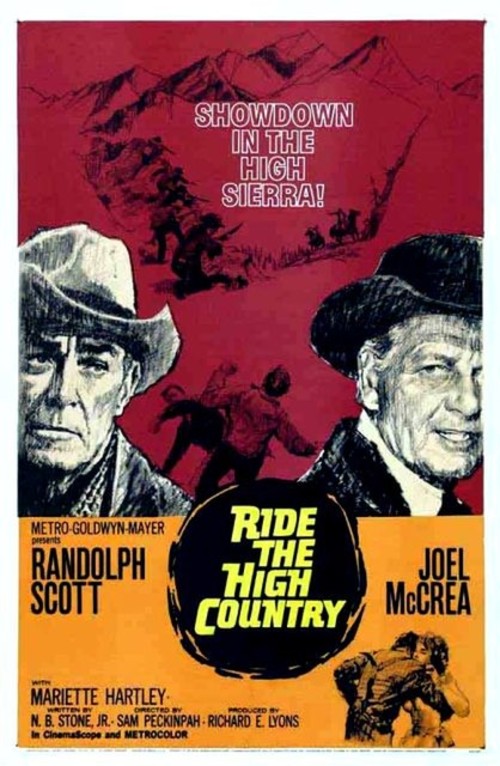

Three years later, Joel was paired with his old friend Randolph Scott in “Ride the High Country,” helmed by a young Sam Peckinpah. McCrea would say of the film: “When it came out the studio didn’t sell it. But the critics grabbed onto it. Neither Randy or I had ever gotten such [positive] criticism. We were surprised, though we knew it wasn’t a regular shoot-’em-up… Both Randy and I were washed-up actors playing washed-up lawmen.”

Joel decided to retire at this point, but eventually was lured back for several more Western roles, making his last appearance in 1976. After that, he and Frances retired to the ranch full-time.

A cowboy in real life, Joel McCrea often played one on-screen. Yet he was so much more than a Western actor. For us, his loyal fans, he’s also Johnny Jones from “Foreign Correspondent,” John L. Sullivan from “Sullivan’s Travels,” and Joe Carter from “The More the Merrier.”

In his hey-day, many of his contemporaries, notably Katharine Hepburn and Bette Davis, felt the industry sorely underestimated his talent. He was also overly modest about his own abilities. Late in life, McCrea admitted: “I have no regrets, except perhaps one: I should have tried harder to be a better actor.”

Joel McCrea, we think you did just fine.