Few artists in the popular culture transcend the passage of time and continue to leave their mark long after their passing. Frank Sinatra is one such performer — a true icon whose indelible renditions of the Great American Songbook you can still hear in films, on the radio, and on the digital playlists of fans, whose ages span from twelve to 102.

Of course, few expected Frank to actually be around for his later birthdays. His ongoing routine of Chesterfields, Jack Daniel’s, and 3AM nightclub shenanigans was no recipe for longevity. More than length of years, clearly Frank cared about making magic and having fun, his way. We were just lucky enough to be there to listen, and to look.

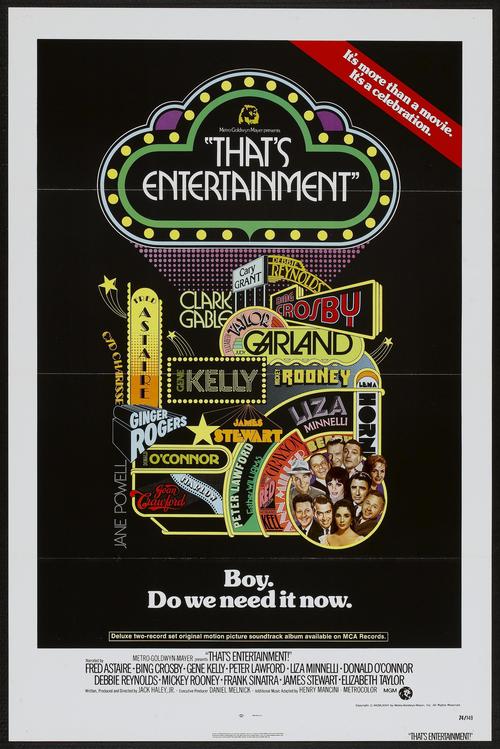

Sinatra recognized early on that to achieve the kind of stardom he sought, he’d have to make his mark in the most powerful medium of all: motion pictures. Having become a top balladeer with millions of female “bobbysoxers” at his feet, Frank began appearing in movies in the early forties, and did a series of light, likeable musicals throughout the decade, culminating in the lively, colorful “On The Town” (1949), directed by Stanley Donen and co-starring Gene Kelly (with whom Sinatra had collaborated twice before, in 1945’s “Anchors Aweigh” and 1949’s “Take Me Out To The Ballgame”).

Then, trouble. With his singing sidelined by a serious throat problem in the early 50s, it seemed Sinatra’s show business days were numbered. A passionate, tumultuous affair with the sultry Ava Gardner and subsequent divorce from first wife Nancy (who’d borne him three kids) further eroded his image and popularity. When his voice-and equilibrium-were finally restored, he had to jump-start his career, and a supporting role in a high-profile movie finally did the trick. (Frank’s desperate lobbying to get this particular part is now the stuff of Hollywood legend).

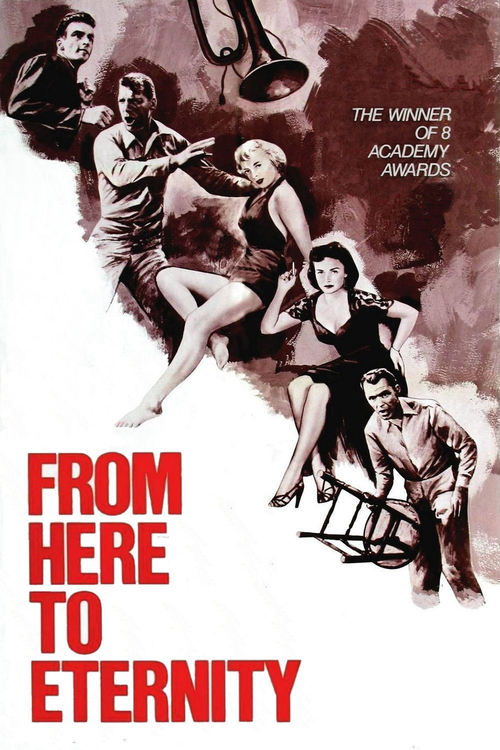

That movie of course was “From Here To Eternity” (1953), Fred Zinnemann’s superb adaptation of the James Jones best-seller about the intersecting lives and romances of various soldiers stationed at Pearl Harbor, leading up to the Japanese sneak attack that finally took our country into World War II. Frank scored in the role of Maggio, a diminutive Italian-American enlisted man with a hot temper. Sinatra’s claim that it was a part he was destined to play was borne out when he netted an Oscar for Best Supporting Actor. Ol’ Blue Eyes was definitely back.

Sinatra was quickly cast to star in “Suddenly” (1954), playing a cold-blooded killer out to assassinate the President. Today, “Suddenly” has the look and feel of a “B” movie quickie, but Sinatra’s intensity blazes off the screen. In an otherwise average picture, Frank excels as a human time bomb set to explode.

After a musical turn opposite the young Doris Day in Gordon Douglas’s entertaining but unremarkable “Young At Heart” (1954), Sinatra the actor shifted into bleak, non-singing territory in Otto Preminger’s then ground-breaking portrayal of drug addiction: “The Man With The Golden Arm” (1955). Sinatra plays Frankie Machine, a rehabilitated junkie who wants to start a new life as a drummer. Yet the presence of his crippled, neurotic wife (Eleanor Parker) and his old pusher (Darren McGavin) undermines his dream at every turn. Only neighborhood girl Molly (Kim Novak) and misfit pal Sparrow (Arnold Stang) really want what’s best for Frankie. Though its treatment of the drug theme feels dated, Frank turns in an astounding performance, earning him his only Oscar nod for Best Actor.

Sinatra then returned to more familiar musical terrain with Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s buoyant adaptation of Frank Loesser’s immortal “Guys and Dolls” (1955). Frank shines as Nathan Detroit, purveyor of the “oldest established permanent floating crap game in New York.” Marlon Brando is better than you’d expect as Sky Masterson, even with some reedy vocals, but you keep waiting for Nathan to show up again.

The next six years would find Sinatra busy in recording studios, doing some of his most enduring music for Capital Records, and on movie sets, making some solid though hardly outstanding films (1957’s “Pal Joey,” 1958’s “Kings Go Forth”).

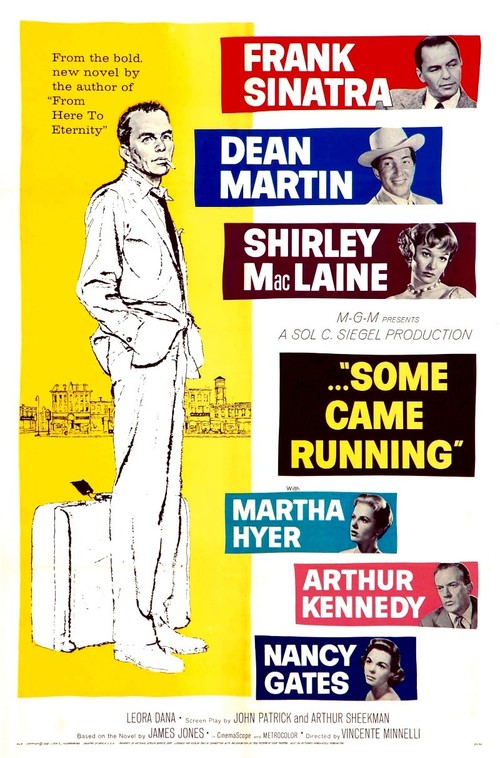

A notable exception is the atmospheric “Some Came Running” (1958), another adaptation of a James Jones novel directed by Vincente Minnelli. Frank plays a World War 2 vet and aspiring writer who has trouble re-establishing himself in his hometown after the war. He meets a good woman (Martha Hyer) and tries to clean up his act, but his acquaintance with adoring Chicago floozie Ginny (Shirley MacLaine) and card sharp Bama Dillert (Dean Martin) undermines the romance. While Frank definitely carries it, Dean matches him scene for scene, and young Shirley is aces.

With the sixties came the Rat Pack series, including “Ocean’s 11” (1960), “Sergeants 3” (1962), and “Robin and the Seven Hoods” (1964), all titles featuring some combination of Dean Martin, Sammy Davis, Jr., Peter Lawford and Joey Bishop, whose enduring value consists of a sort of nostalgic kitsch. These fairly forgettable movies nevertheless offered surface gloss and plenty of attitude, promulgating the “nice ‘n’ easy,” “ring-a-ding-ding” playboy lifestyle Sinatra cultivated in his middle years.

Over this period, Frank would make his greatest film. In John Frankenheimer’s “The Manchurian Candidate” (1962), Sinatra is former Korean War POW Bennett Marco, who’s haunted by nightmares in which fellow prisoner Raymond Shaw (Laurence Harvey) gets ordered by the North Koreans to kill his own men. Seeking out other platoon members afflicted with similar visions, Marco pieces together the fact that Shaw is the linchpin in a deadly communist plot. Twisty and unnerving, all the players are first-rate, particularly Angela Lansbury as Shaw’s evil mother. Frank’s subtle, assured portrayal of Marco signaled a career high point.

It’s been well-documented in countless articles and books that Frank Sinatra the man was a highly flawed, complex individual. His booze-fueled temper tantrums and ill-advised ties to the Mafia have been discussed and debated at length. But leave us not forget the old adage that the only thing a performer really owes his audience is a good performance. If that indeed is true, then Sinatra delivered in spades, both in song and on film.

Frankie, wherever you are, Happy Birthday…and ring-a-ding-ding!

More: Ava Gardner — The One Who Broke Sinatra’s Heart