Today the concept of someone writing and directing their own films is, if not commonplace, hardly unusual. Specific examples immediately come to mind: Billy Wilder, John Huston, Stanley Kubrick, and more recently, Francis Ford Coppola, James Cameron, Spike Lee, and Quentin Tarantino. A quick Google search yields more prominent names.

Today the concept of someone writing and directing their own films is, if not commonplace, hardly unusual. Specific examples immediately come to mind: Billy Wilder, John Huston, Stanley Kubrick, and more recently, Francis Ford Coppola, James Cameron, Spike Lee, and Quentin Tarantino. A quick Google search yields more prominent names.

So it’s hard to imagine that way back in the thirties, during Hollywood’s Golden Age, there was no such animal. Writers and directors were kept in different silos, and never the ‘twain met.

That’s not to say that top directors (not to mention studio brass) didn’t have plenty of input on a given script, but they always had dedicated writers — underpaid, then and now — to go back and actually bang it out.

The late Preston Sturges helped change all that. Having established himself as a gifted screenwriter by the mid-thirties, he commanded top dollar for his services, and then, frustrated by too much interference in his work, resolved to direct the pictures he wrote.

He’d penned sophisticated prestige comedies like 1935’s “The Good Fairy” (directed by William Wyler) and 1937’s “Easy Living” (directed by Mitchell Leisen), then used his leverage to negotiate an unprecedented arrangement with Paramount Pictures: the chance to direct his latest script.

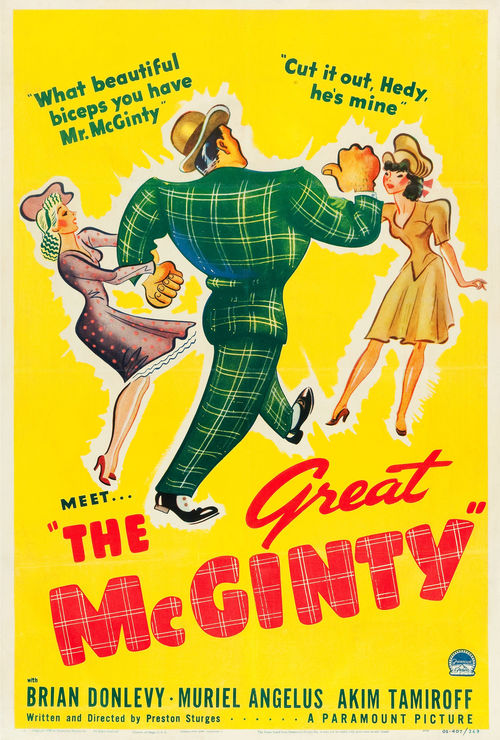

What was in it for the studio? Beyond locking in one of the most talented writers in town, they got a bargain. Reportedly Sturges was paid a grand total of ten dollars for his services on “The Great McGinty” (1940).

His script for that film won an Oscar, and henceforth, for better or worse, Sturges would always direct his own work, while pushing the doors wide open for the likes of Wilder and Huston.

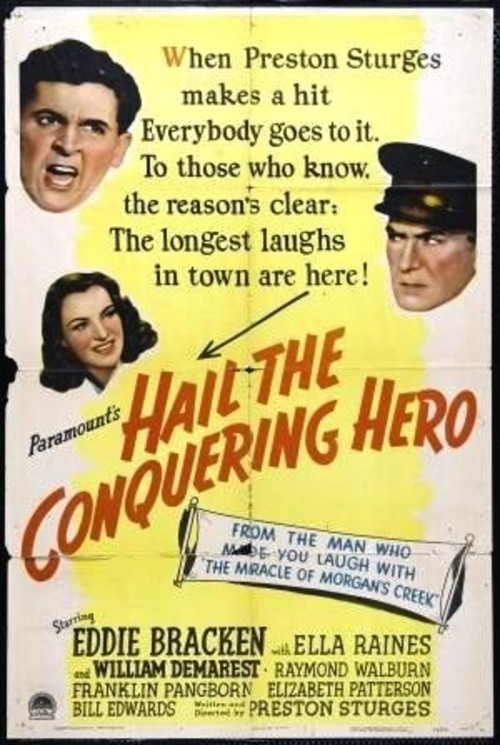

Between 1940-45, Sturges made six enduring comedy classics, earning two more Oscar nods for Best Original Screenplay along the way. But after the Second World War, his winning streak broke, as audience tastes shifted away from the anarchic comedy he was known for.

By that time, he’d made the ill-advised decision to leave his home base at Paramount for an independent gig with the likes of Howard Hughes, equally brilliant and just as erratic. It was a disaster in slow motion.

Unfortunately, when he’d been on top, Sturges had alienated many with his arrogance and extravagance when shooting, with projects often going over budget. Later, when he started to slide, there were few helping hands willing to pick him back up. Failed marriages, bad investments and worsening alcoholism only made things worse.

Sturges never really gave up, but his health suffered. Writing his memoirs alone at New York’s storied Algonquin Hotel in August 1959, he lay down with a bad case of indigestion and suffered a fatal heart attack. He was 60.

His life was as zany and colorful as any of his films. Sturges was born into privilege; his beautiful but eccentric mother Mary Dempsey was a close friend and confidante of famed dancer Isadora Duncan.

Divorced early from Sturges’s father, Mary remarried stockbroker Solomon Sturges, agreeing to live with him for just half a year. The rest of the time would be spent in Europe, mostly with Duncan.

Sometimes she’d bring her precocious son with her, sometimes not. The elder Sturges adopted young Preston, giving him the family name and a small, precious measure of stability.

Mary also started a cosmetics company called Maison Desti, which left even less time for Preston, though eventually he’d work there for a while. From her mother, he’d inherit a keen sense of the absurd, but also a compulsive, reckless quality.

After serving briefly in the First War, Sturges held a variety of jobs, most notably inventing a “kiss-proof” lipstick while at Maison Desti in the twenties He fell into playwriting almost by accident, writing his first play, “The Guinea Pig,” in just under a week. It became a hit on Broadway when he was just 30.

With talkies newly arrived in Hollywood, Sturges was one of countless theater types recruited to head West for sun, fun, and fortune. Soon after arriving, he made a big splash when he sold his original script for “The Power and the Glory” (1933) to Fox Studios for a princely sum.

Right from the start, Sturges surged to head of the pack as a screenwriter, provoking admiration but also envy. His rise would continue for another dozen years.

Today, the best Sturges films still feel fresh, combining fast, clever wordplay, over-the-top characters and a judicious use of slapstick. Better yet, there's real satirical bite underneath all the madcap hilarity.

The three movies listed below, made in 1941 and 1942, remain my personal favorites. All three are listed on the American Film Institute’s list of top hundred comedies (along with one other Sturges entry, 1944’s “The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek”).

These are the first titles I recommend to anyone craving the madcap genius of Preston Sturges. Whether you’re watching them for the first time or the tenth, you’re in for a treat.

The Lady Eve (1941)

In a Nutshell: Father/daughter card sharks (Barbara Stanwyck and Charles Coburn) target the nerdy heir to a brewery fortune (Henry Fonda) on-board an ocean liner. The plot thickens when this slick con woman falls for her mark. The top Sturges movie in my book, “Eve” features a sexy Stanwyck and a peerless Fonda in a rare comedy role.

Did You Know: Reunited for this film after 1938’s “The Mad Miss Manton,” after this shoot Fonda always referred to Stanwyck as his favorite female co-star.

Sullivan’s Travels (1941)

In a Nutshell: A director of successful musicals (Joel McCrea) wants to make a serious drama about poverty and the human condition, much to the chagrin of the studio bosses. For inspiration, he sets out incognito to experience how the other half lives. Along the way, he meets a failed actress (Veronica Lake). Perhaps Sturges’s most personal and powerful film.

Did You Know: Though casting McCrea was unexpected (he was known mainly for Westerns), Sturges always had him in mind for Sullivan, and never seriously considered anyone else.

The Palm Beach Story (1942)

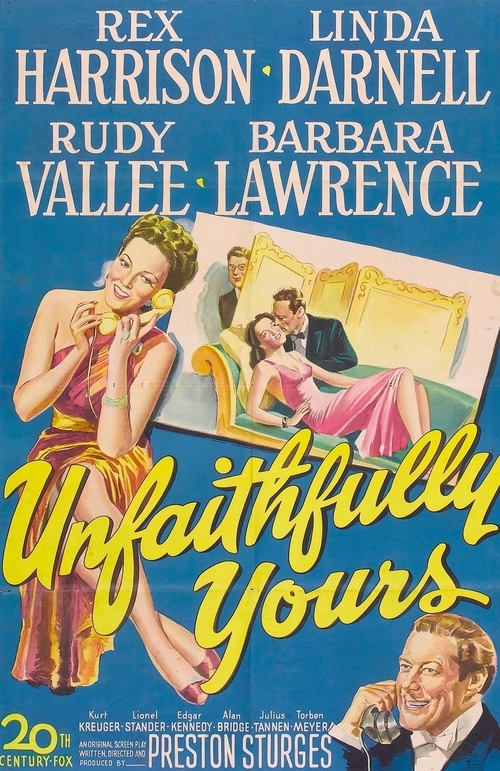

In a Nutshell: Realizing her marriage to a struggling architect (McCrea) is threatened by financial difficulties, a young wife (Claudette Colbert) impulsively decamps for Palm Beach to get a quick divorce. En route she meets a billionaire (Rudy Vallee) who takes a shine to her. Complicating matters is her hubby, who’s in hot pursuit. Fast and funny all the way.

Did You Know: Sturges’s perfectionism caused delays which rankled his Paramount bosses. Lake was also pregnant during filming, concealing her condition with costumes and padding.

More: 6 Talented but Overlooked Directors You Should Know