What it’s about

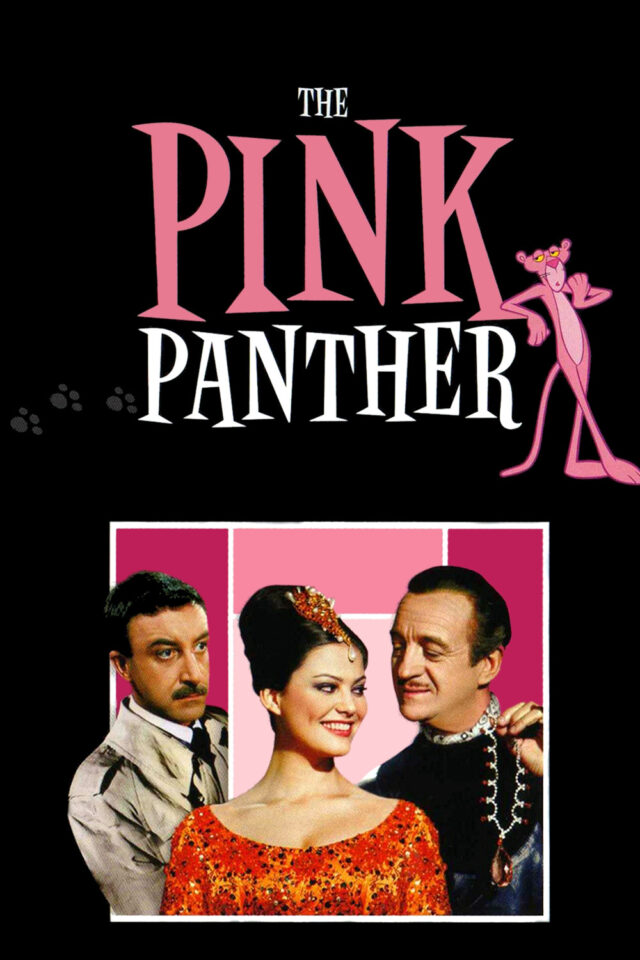

Sir Charles Lytton (Niven) is an ultra-suave jewel thief with his eye on the invaluable Pink Panther, a gem belonging to an Indian princess. Tailed by the bumbling, pratfall-prone Inspector Clouseau (Sellers) at an Alpine ski resort where Princess Dala (Cardinale) is lodging, Lytton will stop at nothing to nab the bauble. But the arrival of Sir Charles’s college-age nephew George (Wagner) complicates matters.

Why we love it

The great Blake Edwards inaugurated the farcical “Panther” series in 1964 with this zesty comedy caper starring David Niven as a covetous jewel thief. But it was Peter Sellers’s brilliant performance as clumsy Inspector Clouseau — the very opposite of Niven’s refined, urbane criminal — that made this a madcap classic. Goofy and fun, with an indelible, Oscar-nominated score by Henry Mancini.

Peter Sellers, David Niven, Robert Wagner, Claudia Cardinale Blake Edwards

Peter Sellers David Niven Robert Wagner Claudia Cardinale Capucine Blake Edwards