Name almost any type of film and it’s likely Robert Wise made at least one of them.

Whether it's a horror movie, a science-fiction outing, a war picture, an ensemble drama, a suspense film or a musical, Wise handled it, usually in exceptional fashion. (The only area he really didn’t tackle was pure comedy.)

Yet predictably, his versatility didn’t play well with some film commentators of his time who prescribed to the “auteur” theory, which lent more significance to directors who consistently followed a signature style in their work.

Wise had this response: "Some of the esoteric critics claim there is no Robert Wise stamp or style. My answer to that is I tried to approach each genre in a cinematic style I think is right for that genre. I wouldn’t have approached ‘The Sound of Music’ the same way I approached ‘I Want to Live!’ for anything, and that accounts for a mix of styles." Makes sense to me.

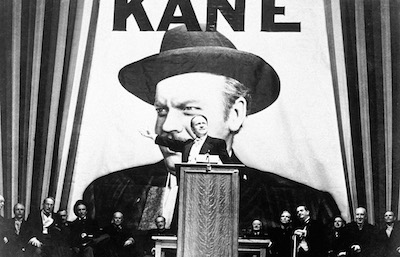

The Indiana native had followed his brother David to Hollywood, where he started his career as a shipper at RKO Pictures. Eventually, Wise worked his way into the sound and film editing suites, where he worked on such groundbreaking films as Orson Welles’ “Citizen Kane” (1941) and “The Magnificent Ambersons” (1942).

Wise, who passed away in 2005 and would have turned 100 on September 10, said simply, “‘Citizen Kane’ was a marvelous film to work on, well-planned and well-shot.” He claimed to have been left alone to handle the editing, although Welles later insisted he was the guiding force in cutting his own masterpiece. The truth is likely somewhere in-between, but since Welles was a filmmaking novice at the time, Wise’s contribution must have been critical, along with cinematographer Gregg Toland’s.

Wise certainly had his scissors out on Welles’s next project, 1942’s “The Magnificent Ambersons.” In fact, Welles was in Rio de Janeiro working on a different picture for the U.S. government when RKO called him to do extensive editing and reshooting on “Ambersons” after a disappointing sneak preview. The new, shorter version of the film was immediately disowned by Welles, while the original, longer version is now considered lost — one of the most famous “lost” films in movie history.

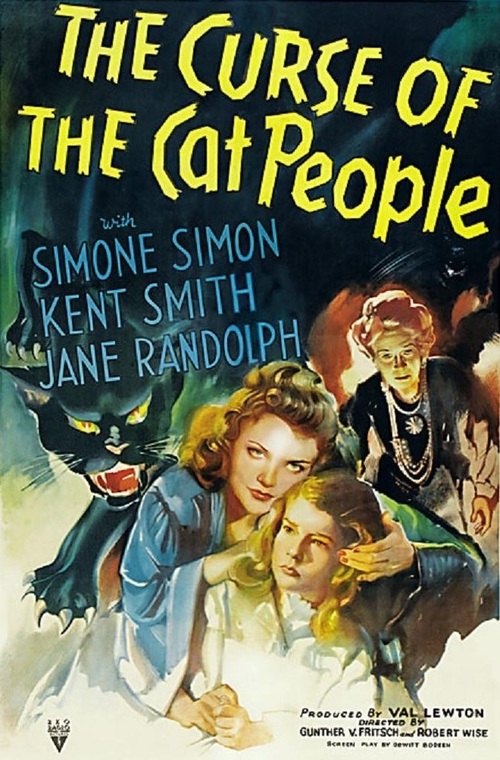

Still at RKO, Wise finally hopped from editing to directing, cranking out atmospheric low-budget horror outings for legendary producer Val Lewton, most notably the cult favorite “The Curse Of The Cat People” (1944).

He then went on to helm some solid film noirs for the studio, as well as 1949’s gritty "The Set-Up,” with Robert Ryan as a washed-up boxer unaware of the corruption going on behind-the-scenes as he gets into the ring one last time. Wise would return to the same arena for 1956’s “Somebody Up There Likes Me,” the biography of juvenile delinquent-turned-middleweight boxing champion Rocky Graziano, played by Paul Newman.

The rest of Wise’s work during this productive period proved that key characters didn’t have to slug it out in the ring in order to elicit emotion from an audience. 1954’s “Executive Suite” featured a stellar cast of performers (William Holden, Barbara Stanwyck, Kirk Douglas, Fredric March and June Allyson among them) in a tale of office intrigue triggered by the death of a company president. Today it plays like an earlier version of “Mad Men.”

Meanwhile, “Run Silent, Run Deep” (1958) teams Clark Gable and Burt Lancaster as feuding officers on a U.S. submarine during World War II. It is chock full of intense moments, and often cited as one of the best underwater adventures ever made. No surprise: both stars play at the top of their games here.

Wise also guided Susan Hayward to the Best Actress Academy Award for “I Want to Live!” (1958), in which she aced the role of real-life party girl Barbara Graham, who stood trial after being accused of murdering a senior citizen.

In the realm of science-fiction and horror, Wise scored with two bona fide classics.

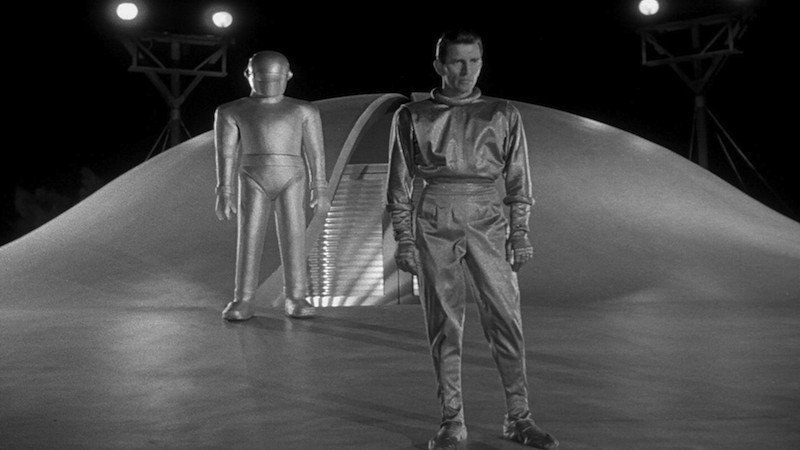

“The Day the Earth Stood Still,” released in 1951, is considered one the greatest science-fiction movies ever made. The story concerns an extra-terrestrial visitation to our nation’s capital: a peaceful, human-like alien (Michael Rennie) arrives by spaceship, accompanied by a destructive robot. His mission is to warn humans about their violent tendencies and how, if they continue, their world will be annihilated. The question becomes: will this advanced being bearing a message of peace escape from our supposedly “civilized” planet?

“The Haunting,” Wise’s 1963 adaptation of Shirley Jackson’s “The Haunting of Hill House,” marked a return to the atmospheric spook-fests he’d made for Val Lewton earlier in his career. The movie, which still chills today, focuses on an eclectic group of people (Julie Harris, Claire Bloom, Richard Johnson, and Russ Tamblyn) investigating the paranormal activities in a ghostly New England mansion where the spirits are willing… to scare the hell out of you! Remade in 1999, we advise you stick with the original.

Wise is still probably best remembered as the man behind two of the most beloved musicals of all time. Along with choreographer/co-director Jerome Robbins, Wise called the shots for the big screen adaptation of “West Side Story” (1961), a musicalized update of the Romeo and Juliet story set against the background of warring New York gangs on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. This electrifying, critically acclaimed release took in 10 Academy Awards, including two for Wise: Best Picture and Director, along with Robbins. (This marked the first time a Best Director Oscar was shared).

Four years later, the director brought Rodgers & Hammerstein’s Broadway hit “The Sound of Music” to the screen, and it swiftly became a sensation. Julie Andrews, who’d just won an Oscar for “Mary Poppins,” took the part of Maria, the novice nun who becomes governess to the seven Von Trapp children. Overseeing this new arrangement is the kids’ strict father, an Austrian naval captain (Christopher Plummer). Though Maria proves a godsend for the family, they are living in perilous times, with the Nazis drawing ever nearer. The film became the most popular movie musical of all-time, winning seven Oscars, including Wise’s two statues, again for Best Picture and Director.

Robert Wise was still making movies well into his eighties. He also held two prominent posts in Hollywood, serving as president of the Directors Guild of America (DGA), and of the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences. In addition to his four competitive Oscar wins, he received the Academy’s prestigious Irving R. Thalberg Award in 1966, given to “creative producers whose bodies of work reflect a consistently high quality of motion picture production.”

That kind of says it all. Auteur or not, Robert Wise really delivered.