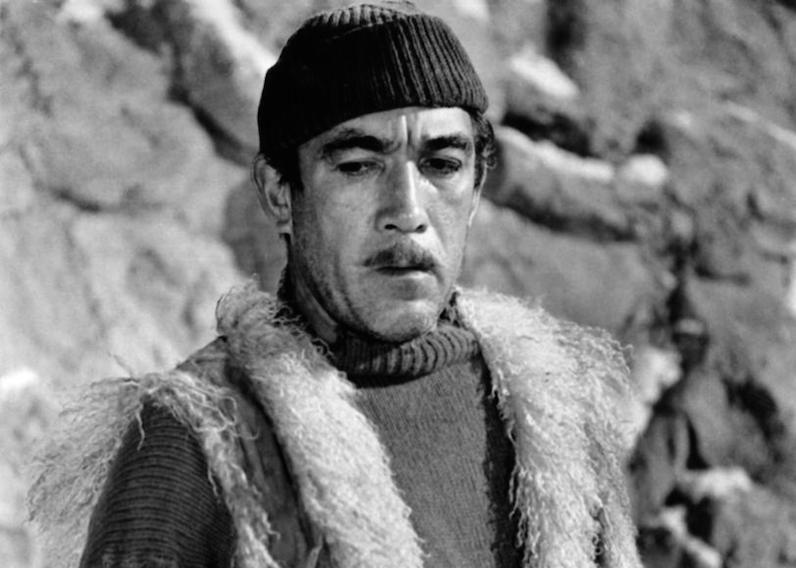

The first time I remember seeing Anthony Quinn onscreen was in 1961’s “The Guns of Navarone.” This World War 2 adventure film remains a personal favorite, and though it features solid performances from Gregory Peck and David Niven, it was Quinn who stood out for me.

Playing a deadly Greek resistance fighter with a score to settle, his authority and intensity pushed all the other players out of the frame. In every scene he was in, my eyes were on him. He himself was well aware of his scene-stealing skills, and told this anecdote of his early days in Hollywood:

“Once I was in a film with a famous star and had to stand behind him in one scene. ‘Now watch that Quinn’, this star told the director, ‘I don't want him stealing the scene behind my back.’ The director parked me in a chair and I just sat there. Next day, when we were looking at the rushes, the star said, ‘See, I told you! Look at him!’ The director exclaimed: ‘But he's only sitting there!’ ‘Only’, rejoined the star. ‘Maybe so, but he's thinking!’”

Quinn was an actor’s actor whose career spanned six decades. He was Oscar-nominated four times, winning twice. In the fifties and sixties, he was that rare phenomenon: a highly respected performer who alternated between leading and character parts with equal ease, and who managed to succeed on his own terms.

His life was every bit as colorful as any role he played.

Quinn was born in Mexico, to a half Irish/half Mexican father and a Mexican mother. His father Frank had fought with Pancho Villa’s troops during the Mexican Revolution; he and his small family eventually escaped over the border to El Paso. From there they ventured to Los Angeles, where Frank eventually found work as an assistant cameraman.

Tragically, Frank was killed in an accident when Quinn was just nine. Tony would attend high school, but wouldn’t finish. Now a tall, strapping young man, he started boxing, and worked a series of odd jobs to earn money. He also took up the saxophone, and played in the orchestra of evangelist Aimee Semple McPherson.

Always talented at drawing, Quinn eventually applied for a scholarship to study with preeminent architect Frank Lloyd Wright. Against stiff competition he was selected, and for a time Tony worked closely with Wright. One day, Wright suggested that his new pupil take acting lessons to fix a slight speech impediment.

Quinn signed up, and it was quickly evident that his true calling was acting not architecture. At the age of 21, after a brief training period in the theatre, Anthony Quinn found himself in the movies. From the start, ethnic characters and villains were his specialty, due to his dark, exotic appearance.

You can glimpse Tony as a Native American warrior in 1936’s “The Plainsman,” directed by Cecil B. DeMille. Roughly one year later, he would marry DeMille’s adopted daughter Katherine. Just as his Irish surname had prevented Tony from being fully embraced by the Mexican- American community, now his Mexican ancestry ensured he would never be fully accepted by his famous father-in-law. Still, his marriage helped introduce him to some of the most powerful players in Hollywood.

While he stayed busy in supporting roles over the next decade, stardom eluded him in Hollywood. With the Second War over (Quinn was exempted from the draft as a Mexican national), a Communist backlash began in Hollywood. Though not an outright Communist, he knew quite a few, and decided he wanted to avoid the whole mess. A change of pace would be welcome anyhow. Tony headed to New York.

What happened there transformed his career. A young actor named Marlon Brando had just changed the nature of theatre forever playing the loutish Stanley Kowalski in Tennessee Williams’s “A Streetcar Named Desire.” Director Elia Kazan met Tony, and soon decided his raw physicality made him the ideal replacement for Brando. It was a hit for Quinn — and better yet, he, Kazan, and Brando would soon meet again.

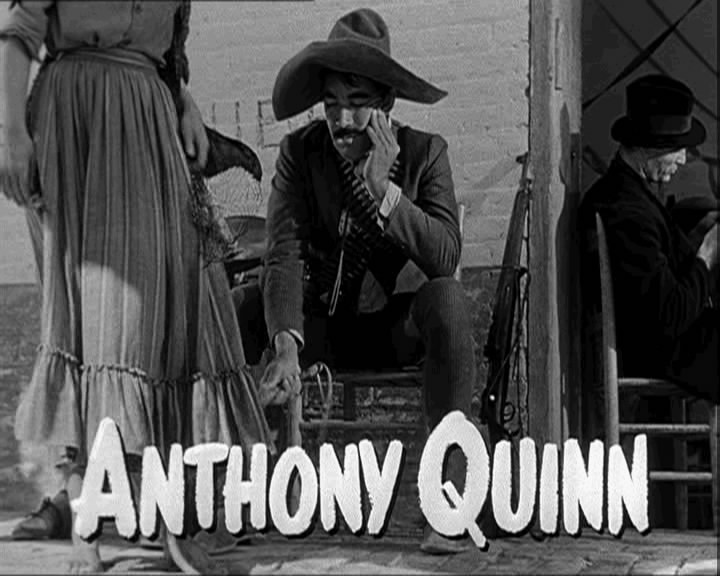

Tony returned to Hollywood in the early 50’s to do some tough guy roles. He was also getting work in the new medium of television. The Mr. Kazan came calling again. Brando had just been cast to play Mexican revolutionary Emiliano Zapata in his next film, and the director wanted Quinn for the leader’s hotheaded brother. Tony would win his first Oscar — and new prominence in Hollywood — for “Viva Zapata!”

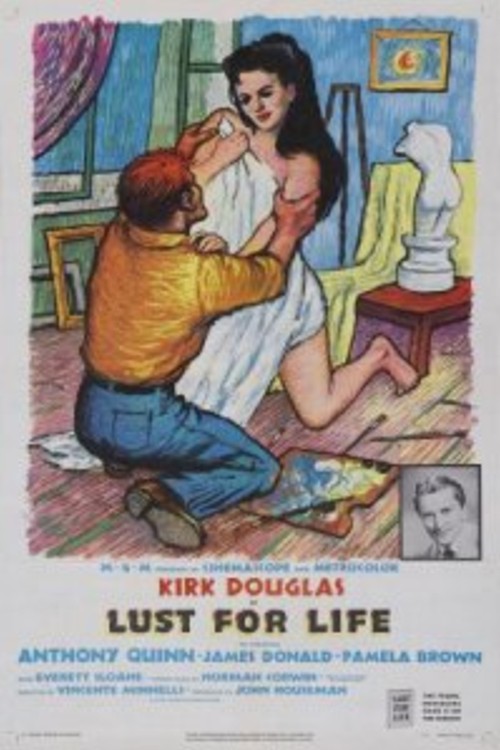

His success opened up new vistas, and he signed on to play Zampano, the traveling carnival strongman, in Federico Fellini’s classic “La Strada” (1954), opposite Fellini’s wife, Giulietta Masini. Back in Hollywood two years later, he’d win his second Oscar playing Paul Gaugin opposite Kirk Douglas’s Vincent Van Gogh in “Lust for Life.”

Other great movie parts followed in the years to come, most memorably Andrea in “Navarone,” warrior Auda Abu Tayi in David Lean’s “Lawrence of Arabia” (1962), and Alexis Zorba in “Zorba the Greek” (1964). This last role, that of an open-hearted Greek peasant, would become his best-known work and win him his last Oscar nod. He would even reprise it in a musicalized stage version two decades later.

All the while, he was a man searching, living in different places, trying on different masks. Quinn himself was surprisingly self-aware about it: “One of the reasons I did all the Greek and Arab parts was because I was trying to identify myself as a man of the world. I lived in Greece, in France, Iran and all over the world, Spain, trying to find a niche where I would finally be accepted.”

Quinn’s personal life betrayed this same restlessness. In 1965, Quinn finally divorced Katherine, with whom he’d had five children (the oldest of whom had drowned in neighbor W.C. Fields’s pond at the age of two). He married his mistress Jolanda Addolori in 1966, and they’d go on to have three children. While still married to Jolanda, he had two kids with another companion, Freidel Dunbar. Then in 1997, he divorced Jolanda and wed his much younger secretary, Kathy Benvin, who’d bear him two more kids. Thus Quinn had a total of 12 children with four different women, 11 of whom would grow to maturity.

Tony had an outsize machismo that, as time went on, seemed increasingly out-of-date and misguided. Like his contemporary Frank Sinatra, he admired the Mafia, counting several major underworld figures among his friends. He visited the John Gotti trial, hoping to meet the Teflon Don. And later in life, he expressed disappointment in his own sex by saying: “I don't see many men today. I see a lot of guys running around on television with small waists, but I don't see many men.”

Quinn would never allow himself to retire but as his career started to wane in the late seventies, he devoted more time to creating art and soon established himself as a highly respected painter and sculptor. By all accounts this gave him much more pleasure than acting.

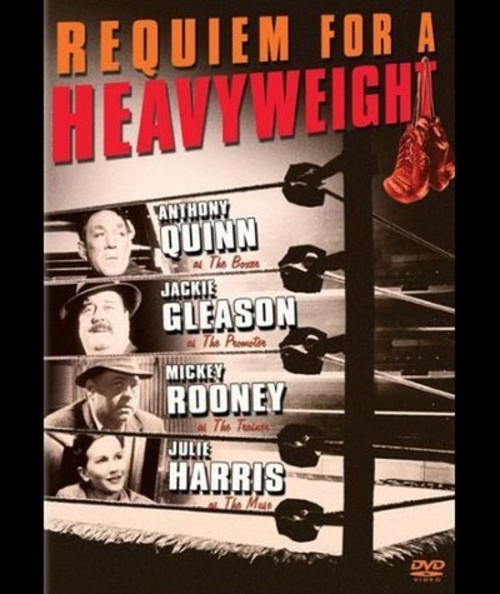

In 1996, just a few years before his death from throat cancer at the age of 86, he said: “The painter leaves his mark. I just put in two statues in Rhode Island that I'm working on. And I think that's going to make me last longer than me. I mean, who remembers ‘Zorba’? Nobody remembers ‘Zorba’. Nobody remembers ‘Requiem for a Heavyweight.’”

Mr. Quinn, we respectfully disagree.

More: The Sad History of Hollywood's Wild One: Marlon Brando