If you’re like me, a handful of movies are lodged in your memory that strike a special cord. These are the titles that made a big impact early on and never left you.

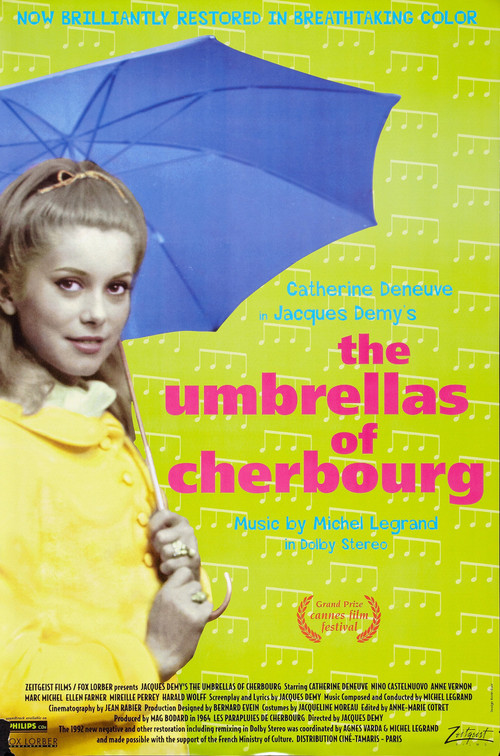

Among my own short list of prized cinematic gems is Jacques Demy’s musical romance, “The Umbrellas of Cherbourg” (1964). My family was still living in Paris when it was shot, and over half a century later, I can still remember the cover of the soundtrack album, which we played endlessly.

As I’ve revisited “Umbrellas” over the years, I’ve found myself more affected and moved by it each time. This is hardly surprising, since as we age, nostalgia for the memories of our youth- the experiences that shaped us- becomes ever more powerful.

Critic Jim Ridley, who’s seen “Umbrellas” many times, observed: “When I watch it now, it reminds me of the doorjamb in my grandmother’s house with my height marked in pencil over the years, or the dresser with my own children’s measurements notched along the edge. In it I see the person I was and the person I have turned out to be, but the object itself will always be the same.”

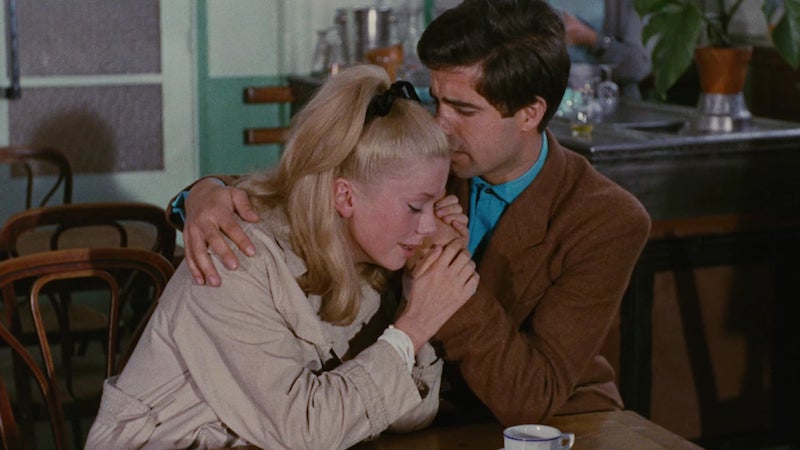

Set in the late fifties, “Umbrellas” tells the story of garage mechanic Guy (Nino Castelnuovo) and the stunning Genevieve (Catherine Deneuve), a young woman of seventeen who works in her mother’s umbrella shop in the French port city of Cherbourg.

The two experience the pangs and passion of first love, but their relationship gets interrupted when Guy is drafted to fight in the Algerian War. Will their affair survive an extended separation of two years?

(The story was highly personal for Demy, who grew up in another port city, Nantes, and whose father was a mechanic who operated a garage right next to the Demy home).

The plot, however, takes a back seat to both the style of the film, shot in saturated pastels in tribute to the fifties Hollywood musicals Demy adored, and to the achingly beautiful soundtrack which runs throughout, created by composer Michel Legrand.

Oh, and did I mention the film is all-sung, like an opera? That’s right: no spoken dialogue.

Much as he revered those MGM technicolor extravaganzas, Demy felt that alternating spoken dialogue with song and dance, as those movies always did, could actually compromise the smooth progression of a story. His theory was that an all-sung musical, done right, could be absolutely seamless.

Most everyone he spoke to about his idea thought he was crazy. It hadn’t been done before for a good reason: no one would ever come see such a film.

How would Demy ever get financing? He had two relatively successful features behind him by this point, but this only went so far.

With the French New Wave in full swing, colleagues like Godard and Truffaut were breaking fertile new ground with their work, and here was Jacques, proposing an all-sung, Hollywood-style musical. He seemed decidedly out of step with the times.

However, both Demy and Legrand were still in their early thirties, just young and foolish enough to believe it could work. But when they both sat down to begin creating “Umbrellas,” nothing came easily at first.

The fact that every word in the script had to be set to music proved daunting at first. After some torturous sessions that produced only frustration, Demy and Legrand finally hit their groove.

Then, once they had the score, the real fun began as the two men went around to every producer they could think of in search of funds. Legrand would perform the whole movie on the piano, singing all the characters, while Demy stood beside him, dutifully turning the pages.

It was exhausting, and they were shown the door more than once. Finally, they were pointed to Mag Bodard, a producer with just one other film to her credit, who agreed to take on the project.

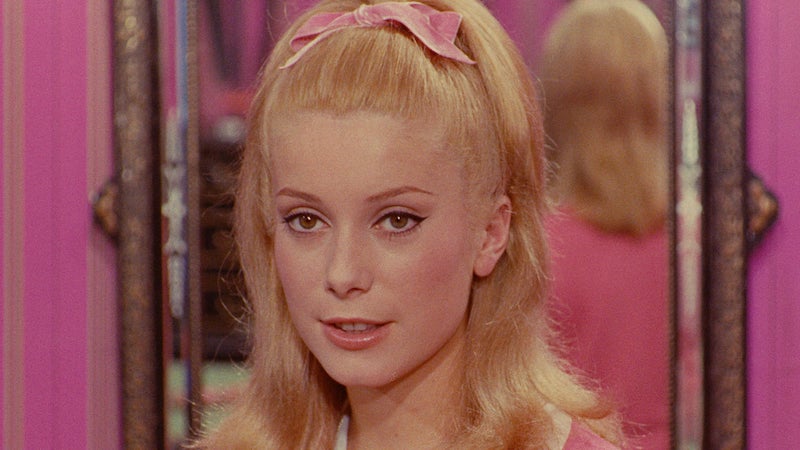

The casting of Catherine Deneuve as Genevieve was an early masterstroke. But soon the twenty-year-old ingenue, in her first starring role, began feeling uneasy.

First, she had always worn bangs and felt this was integral to her image. However, Demy wanted a fresh innocence for Genevieve, so the bangs had to go. Deneuve was crestfallen, and felt “exposed” with her beautiful forehead in full sight.

For her and others in the cast, the rehearsal process also required some adjustment. None of the onscreen actors could sing; all had to be dubbed. So Deneuve and Danielle Licari, the singer hired to voice Genevieve, went into the recording studio and worked together to capture just the right tones and inflections throughout the score. The other featured players collaborated with their singing counterparts in exactly the same way.

Once the complete soundtrack was recorded, each on-screen actor received a record of it and then had to play and re-play it in front of a mirror, lip-synching their part. Then on set, the record was played as the scenes were shot.

Anne Vernon, who portrays Genevieve’s mother, noted how challenging it was since there was no room for pauses or unexpected bits of business to create a feeling of spontaneity. Their performances had to follow the score, note for note.

The task of getting the costume and set design just right was equally painstaking. In scene after scene, eye-popping greens, blues and oranges merge in wardrobe and wallpaper. Often a vibrant dress pattern would inspire the wallpaper directly behind it. It took ages to get everything to coordinate and blend together to Demy’s satisfaction.

Beyond its aural and visual brilliance, it’s noteworthy just how poignant “Cherbourg” is, a far cry from the likes of “Singin’ in the Rain” and “The Band Wagon.” First, when Guy is drafted, he leaves Genevieve pregnant, out of wedlock. When her mother eventually pushes Genevieve toward the older, successful businessman Roland Cassard (Marc Michel, a character we’d met before in Demy’s “Lola”), it’s partly because the umbrella shop is failing and she needs the money.

Basically, she is auctioning her daughter off to the highest bidder. This works because it’s done subtly, without spoiling the fantasy of this magical world, filled with vibrant color and song. Also, we never once lose sympathy for the characters.

The ultimate triumph of “Umbrellas” is that it actually was a triumph. The film which so many industry experts had bet against was an immediate hit, not just in France but internationally, winning the top prize at Cannes, and five Oscar nominations, including Best Foreign Language Film.

It shot Deneuve to stardom, and introduced two Legrand standards that have been widely covered since: the heartbreaking “I Will Wait For You” and “Watch What Happens.”

Still, the boldness of its conceit undermines its complete acceptance, even today. I myself have hesitated about introducing “Umbrellas” to some of my friends. Will they see what I see, or will they laugh at the fact that everything is sung, including mundane lines like “You smell of gasoline”? Will they think it too sentimental and gooey?

Most always I’ve conquered these fears and taken the plunge. I am happy to report that so far, no one has dismissed or disengaged from this gorgeous, deeply touching film.

Critic Pauline Kael noted in 2000 that “one of the sad things about our times, I think, is that so many people find a romantic movie like this frivolous and negligible. They don’t see the beauty in it, but it’s a lovely film — original and fine.”

I couldn’t have said it better if I tried.

More: Blonde on Blonde — 30 Dazzling Photos of Catherine Deneuve