Before Penn and De Niro, before Brando and Dean, there was John Garfield. Virtually forgotten today, he introduced an intense realism to movie acting in the 1940s, born of training and talent, that would inspire these later stars. Then, just as Garfield’s career was soaring, he became a victim of the notorious “Red Scare” at the dawn of the fifties. All too quickly, it was over.

Garfield had an edge, a toughness, and it was well earned. Born Jacob Julius Garfinkle in 1913, the son of Russian-Jewish immigrants, he grew up in poverty on the hard streets of New York City’s Lower East Side. His mother died when he was just seven, and he spent the rest of his childhood being shuttled among various relatives.

By his early teens, he’d joined a gang and been expelled from more than one school. He ended up at P.S. 45, which specialized in young people with disciplinary problems. Teachers there soon saw something special in Julie (as he was always known).

He was enrolled in a speech class to fix his stammer. After that, his gift for mimicry was noted, and he was encouraged to take acting classes. His natural gifts soon became evident. He won second place in a student debate sponsored by The New York Times. He had presence, and he loved language. Suddenly, his destiny seemed clear, a realization that happened just in time. As Garfield wryly noted years later of his wild younger years, “If I hadn’t become an actor, I might have become Public Enemy Number One.”

He continued studying acting after high school, but by now, the Depression had hit, and even with talent, it was hard to get work. After a brief stretch hopping freights around the country, he came back to New York, and set his sights on the stage. He made his Broadway debut in 1932, then got a featured role in “Counsellor at Law,” starring Paul Muni, which would soon become a screen vehicle for John Barrymore. (It was in this play that Warner Brothers first spotted the promising young actor, as Muni himself was on the Warner roster.)

Julie’s specific ambition was to join “The Group,” a fledgling theater company founded by Harold Clurman, Lee Strasberg and Cheryl Crawford. This team of young actors, writers, directors, and producers — many of whom would become famous — were pursuing a bolder, grittier, more socially aware form of drama. Initially rejected several times, Julie persisted, and was finally accepted.

His breakthrough came with The Group’s production of Clifford Odets’s “Awake and Sing!” in early 1935, which concerned a struggling Jewish family in the Bronx. Julie won critical praise for his portrayal of the family’s idealistic son. Odets, who had known Julie for years, championed him at first, but when he was passed over for the lead in his next play, “Golden Boy,” Julie started considering the Hollywood offers that had been coming his way.

Negotiations with studios had always stalled over Julie’s insistence that he be allowed time off to do stage work. Now, Warner Brothers finally decided to accept that provision. With many of his colleagues in The Group complaining that he was selling out, Julie and his new wife, childhood sweetheart Roberta Seidman, set out for the West Coast. There his name was swiftly changed to John Garfield.

Garfield made a big impact with his first featured role in the musical drama “Four Daughters,” winning himself an Oscar nod for Best Supporting Actor. Though the studio started to build him up, they did not find him easy to work with, largely because of his willingness to reject roles in inferior pictures, even if it meant suspension. As he put it, “I was suspended ‘only’ 11 times. I served my time and took it like a sport . . .They taught me the business, and they made me a star. They took their chances with a cocky kid from the East who still talked out of the corner of his mouth. I appreciate all that.”

When World War 2 intervened, Garfield immediately tried to enlist, but was rejected due to a bad heart. (He’d suffered a bout of scarlet fever as a youth.) He settled for playing servicemen in the movies, which he did admirably in 1943’s “Destination Tokyo” and 1945’s “Pride of the Marines.” To support the war effort, he and Bette Davis also co-founded the Hollywood Canteen, a place where servicemen could go to dance and be entertained.

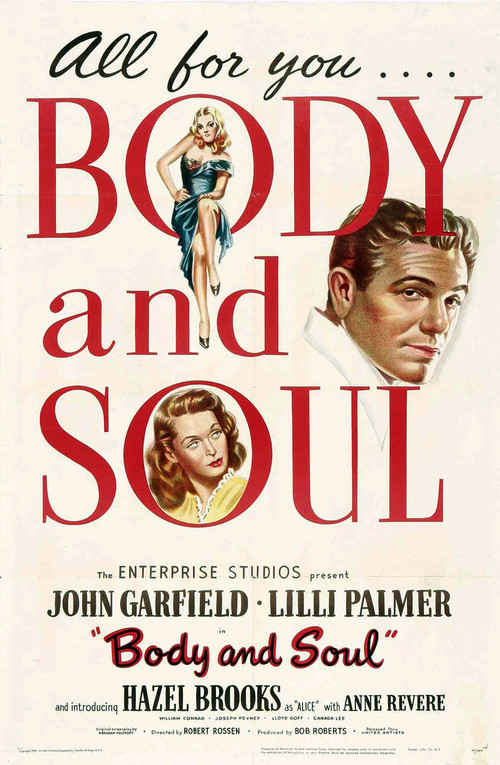

Garfield’s most enduring work came in the five years after the war. Suddenly films were projecting a darker mood which brought out the actor’s volatility and brooding intensity. His performances in classics like “The Postman Always Rings Twice” (1946) and “Body and Soul” (1947) hold up beautifully to this day.

After his second Oscar nod for the latter film, John Garfield should have been on top of the world. Yet storm clouds were forming. Along with 150 others (including Orson Welles, Edward G. Robinson, and fellow Group theater alum Lee J. Cobb), Garfield’s name was published in the notorious anti-communist brochure “Red Channels” in 1950.

He was forced to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1951, denied being a communist and refused to name names, claiming he knew no communists in the industry. His unwilligness to supply useful information meant his film career was effectively over.

The stress took its toll. In May of 1952, Garfield separated from his wife (they’d had three children since his arrival in Hollywood). About a week later, against doctor’s orders, he played several strenuous sets of tennis. The next morning, he was founded dead of a heart attack. He was just 39.

Garfield once said that no actor could do his best work before the age of 40. It’s eerie that he left us just a few months short of that milestone. You have to wonder about all the amazing portrayals that might have been, had one heinous act of injustice — the Hollywood blacklist — not cut short the life and career of John Garfield.

More: How Elia Kazan Became One of the Most Influential Directors in Hollywood