Early in 1973, producer David Brown was scanning the literature section of Cosmopolitan, a magazine edited by his wife, Helen Gurley Brown. His eyes fell upon a brief plot description of an upcoming novel by Peter Benchley called “Jaws,” which concerned an immense great white shark terrorizing a New England resort community. The book editor ended his summary as follows: “Might make a good movie.”

Brown agreed and immediately requested an advance copy of the book for himself and his partner, Richard Zanuck. Both were excited by what they read, and quickly snapped up the rights for $175,000. They then closed a deal with Universal Studios to finance and distribute the picture.

Little did they realize what challenges they’d face in bringing “Jaws” to the screen.

The team first hired Dick Richards to direct, but dropped him after a few story conferences where Richards kept referring to the shark as a whale. Then a young up-and-comer named Steven Spielberg expressed interest, having seen the “Jaws” galleys on Brown’s desk. At first, Spielberg wondered whether the script was about a dentist.

Zanuck and Brown had just finished working with the twenty-six-year-old wunderkind on his first theatrical feature, “The Sugarland Express,” and had been impressed with Spielberg’s creative instincts and drive. They decided to give him the assignment.

Author Benchley wrote the first draft of the screenplay, and after two more drafts, said he was “written out.” Spielberg’s goal at that point was to make Benchley’s characters more likable, add leavening humor to the story, and eliminate subplots that detracted from the main premise.

Though the final script is credited to Benchley and comedy writer Carl Gottlieb, many others contributed along the way. Once production started, rewrites would occur the night before shooting specific scenes, and ad-libbing was encouraged. The delays that would later plague “Jaws” at least allowed time to refine the script. This would pay off in the finished product.

In terms of casting, the goal was to avoid mega-stars. Spielberg wanted the audience to believe that this calamity was happening to real, relatable people. In his view, the star of the film would be the shark.

The first role cast was Chief Martin Brody, a big city cop who, ironically, is terrified of the water. Spielberg first wanted Robert Duvall, but the actor declined. Charlton Heston lobbied hard for the part, but he violated the “no big star” rule. (Heston was reportedly furious at being turned down).

Spielberg had seen Roy Scheider in “The French Connection” (1971), and admired his performance. Coincidentally, Scheider was at a party the director was attending and overheard him talking about a sequence where the shark jumps onto a boat. The actor’s interest was piqued, and he was soon tapped to play Brody.

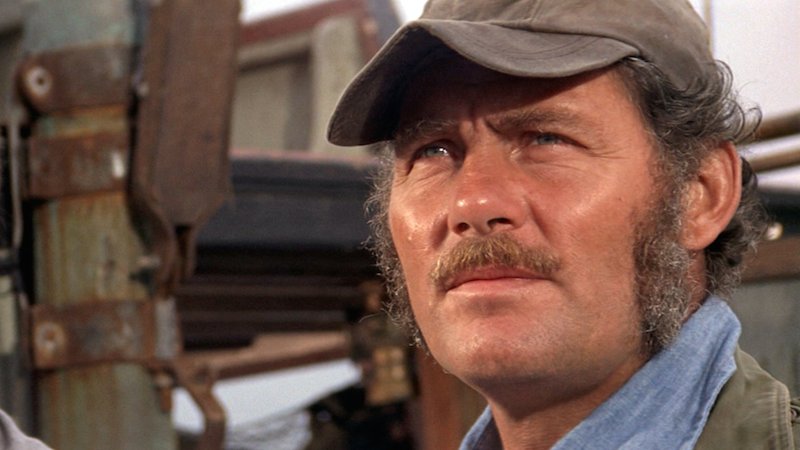

Ten days before shooting was to begin in May, 1974, the other two main roles — grizzled shark hunter Quint and youthful oceanographer Matt Hooper — had yet to be cast. The producers had specified Lee Marvin or Sterling Hayden for Quint, but both passed. Brown and Zanuck then thought of British actor Robert Shaw, who’d just appeared in their hit film “The Sting.” After some initial hesitancy, Shaw signed on.

As to Hooper, Jon Voight was first choice, and a young Jeff Bridges was also considered. Then Spielberg’s pal George Lucas recommended Richard Dreyfuss, the star of Lucas’s yet-to-be-released “American Graffiti.” Spielberg clicked with Dreyfuss, and would come to view him- and his character- as his alter ego in the film.

Just in the nick of time, the director had his three stars.

That the principals had no idea what they were up against is reflected in the initial production schedule, which called for 55 days of shooting on Martha’s Vineyard. The shoot would actually last 159 days, due to a variety of mishaps.

Meanwhile, the film’s budget would eventually soar from four to nine million dollars. Few if any Hollywood directors had gone that far over an original budget and schedule, and Spielberg worried his career might be over before it had truly begun.

The first major issue was the star himself- specifically, three mechanical sharks named “Bruce,” after Spielberg’s lawyer. Constructed by Bob Mattey, who’d created the giant squid in 1954’s “20,000 Leagues Under the Sea,” the sharks had only been tested in fresh water before being shipped to the location. Big mistake.

Once they were placed in the ocean, they promptly sank to the bottom and had to be retrieved. Then the salt water wreaked havoc on their insides, and they rarely functioned properly. Spielberg quickly realized that he’d have to channel Alfred Hitchcock and create fear and suspense through what was not seen. Though it seemed like a daunting task at the time, it inspired some ingenious ideas that actually improved the film. (Just consider that terrifying opening scene with the female skinny-dipper being violently dragged across the water. We never see the shark, but we sure feel its presence).

Shooting on the water was also unexpectedly difficult. Over the course of a twelve-hour day, on average Spielberg would get just four hours of footage. Cameras got wet and boats popped into the frame. (Spielberg wanted the characters to feel totally isolated at sea, with no other vessels or land in sight). At one point, Quint’s boat, the “Orca,” had a hole torn in it and started to sink, with cast and crew aboard. Personnel and equipment were rescued with no time to spare.

There was friction among the cast as well. The brilliant Robert Shaw, charming when sober but combative when drunk, took an early dislike to co-star Dreyfuss and needled him constantly. Though this helped generate the necessary animosity between their two characters on-screen, it also put everyone on edge.

Shaw based his performance on local fisherman Craig Kingsbury, who also has a small role in the film. Several of Kingsbury’s spontaneous utterances were picked up and incorporated into the script. Without question Quint rates as one of Robert Shaw’s finest performances, with his mesmerizing speech about the sinking of the U.S.S Indianapolis during World War Two a particular highlight. Few realize that Shaw, who was also a playwright, crafted the final version himself.

Viewing that sequence in the daily rushes, Spielberg finally realized that a great movie was coming together. This was only confirmed in post-production when the talents of veteran editor Verna Fields and composer John Williams came into play.

For the score, Williams had settled on two alternating bass notes that could be slowed down or sped up according to the scene. Hearing it the first time, Spielberg thought it was a joke and asked Williams what he really had in mind. Williams patiently explained that the theme perfectly mirrored the shark “grinding away at you…instinctual, relentless, unstoppable.”

Williams earned an Academy Award for his contribution, and Spielberg later admitted that the score made the film twice as effective. He and Williams would form an enduring partnership, collaborating on a total of 26 films as of this writing.

When production finally wrapped in the late fall of 1974, Spielberg and company were not given a hero’s welcome back at Universal. It was no surprise that the brass had become frustrated with all the cost overruns and delays. The prevailing sober mood only reinforced how much was riding on the success of “Jaws”.

However, all the pressure and worry began melting away after a series of test screenings where audience response was overwhelmingly positive. A few minor adjustments had to be made, but it was clear they had a hit on their hands. (Benchley’s book had become a runaway bestseller, which also helped).

Because of the movie’s extended production period, “Jaws” would have to premiere in the summer, traditionally the time when studios dumped their worst product on the market. Now excited about the final film, Universal decided to invest in a huge marketing campaign, including a soundtrack album, tee-shirts, games and other merchandise.

They also planned to go for a wide release, close to 900 screens simultaneously, until Universal chairman Lew Wasserman ordered that number halved, stating: “I want this picture to run all summer long. I don’t want people in Palm Springs to see the picture in Palm Springs. I want them to have to get in their cars and drive to see it in Hollywood.”

“Jaws” opened on June 20, 1975, to booming business and mostly positive reviews. Roger Ebert called it “a sensationally effective action picture, a scary thriller that works all the better because it’s populated with characters that have been developed into human beings.”

The film recouped its production costs in two weeks. In just under three months, it became the first movie in history to break the $100 million mark in theatrical rentals. Forty years after release, its total grosses approach $500 million.

It also scored four Oscar nominations, including Best Picture, and won for editing, music, and sound. It was, in the view of many, a serious oversight that the Academy failed to recognize Spielberg and Shaw for their amazing work.

In film history, the significance of “Jaws” extends well beyond its astonishing commercial success. It marked the beginning of the summer blockbuster era. Now, between Memorial and Labor Day, we can expect a series of big, loud, “high concept” movies that cost over a hundred million dollars to make but yield handsome profits in wide release, both here and abroad. Sadly, very few of them are as good as “Jaws.”

Ultimately, the story of how this movie got made is almost as fascinating as what ended up on the screen, demonstrating the essential wonder of high stakes moviemaking: how an incredibly challenging, haphazard production beset by technical problems, major delays and ballooning budgets could yield a masterpiece of terror whose impact has not dissipated with time.

Forty-plus years after its initial release, “Jaws” remains the greatest summer movie of them all.

More: "The Wizard of Oz" — Why Our Most Beloved Film Was So Hard to Make