Doing what I do, people frequently ask me to name my favorite movie. It sounds like a reasonable request, but for me it’s maddening because there are so many fabulous movies that attain the same level of superiority, but are wildly different. I find it very hard to pick just one.

That said, if someone forced me to compile a top ten list, Billy Wilder’s “The Apartment” would definitely make the cut. While I’d watch it most anytime, it’s also a film that particularly resonates at holiday time. It is the ultimate New Year’s Eve film.

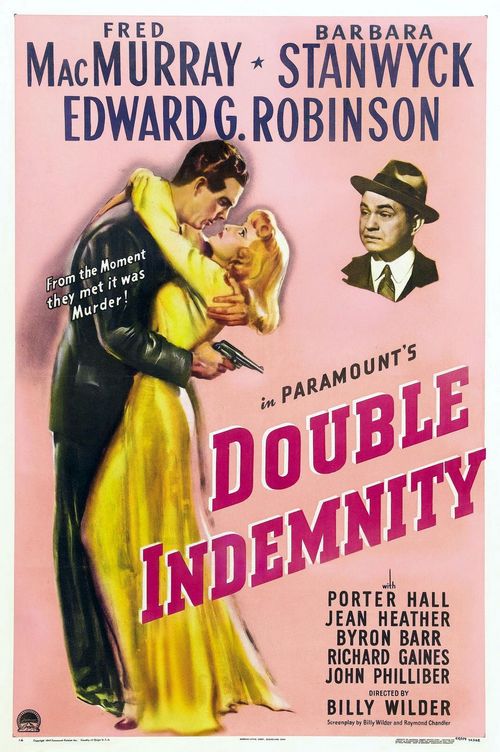

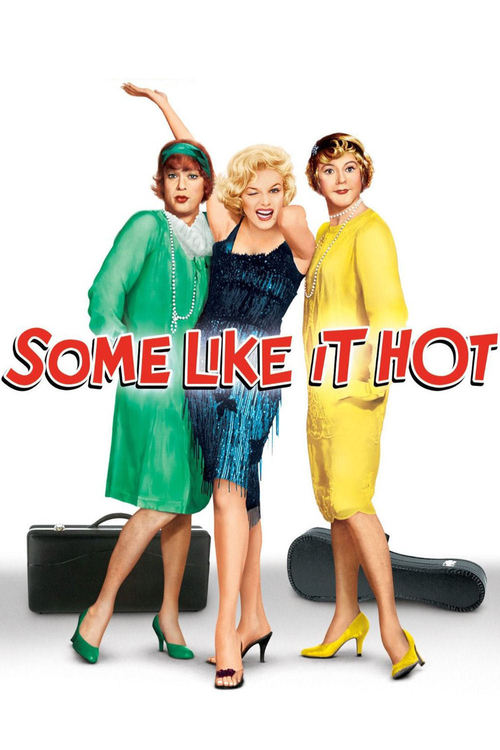

Though movie buffs revere it, several other Wilder films are better known today: certainly “Some Like It Hot” (1959), Wilder’s prior outing with Jack Lemmon the year before, as well as “Double Indemnity” (1944), “Sunset Boulevard” (1950), and “Sabrina” (1954). I love these other titles, but none exert the hold on me that “The Apartment” does.

It has always baffled me that many critics refer to it as a romantic comedy. I view it as a serious adult drama with comedic elements. Like another holiday movie, “It’s a Wonderful Life,” “The Apartment” is actually a very deep and dark film, dealing with human isolation in an increasingly modern, mechanized world. It’s a theme that’s only more relevant today.

As with all the best Wilder films, story and script carry the day. Wilder had started in Hollywood as a writer, chalking up screenwriting credits for such classics as “Ninotchka” (1939) and “Ball of Fire” (1941). Once he became a director, he earned a special prestige in the industry by writing all his scripts, most always with a partner: first Charles Brackett, then I.A.L. Diamond, who worked on this picture. (Few other writer/directors existed in those days- Preston Sturges was one, but his output tapered off in less than a decade.)

“The Apartment” centers on the plight of C.C Baxter (Lemmon), a junior insurance man in a huge firm. One random act — lending his apartment to a superior for a “meeting” — turns into a flood of executives wanting to use Baxter’s apartment for their assignations. The good news: Baxter gets noticed by the higher-ups, who promise him a promotion. The bad news: he does not get to use his apartment much.

Seemingly Baxter has no family, no friends, no ties, so the holidays in Manhattan only exacerbate the loneliness he feels all year round. Still, he’s ambitious, an anonymous guy who does not want to remain so. He wants to break out and move up, even if he has to compromise his morals in the process.

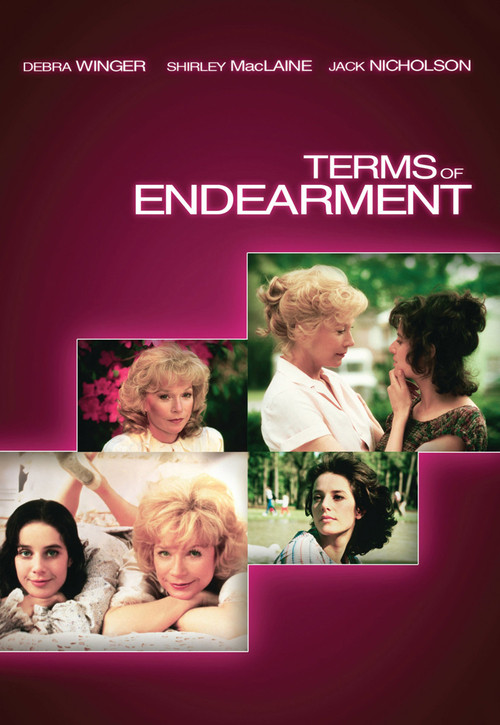

But he’s also touchingly human, desperate for real connection. He becomes infatuated with elevator girl Fran Kubelik (Shirley MacLaine), but unbeknownst to him, she only has eyes for the big boss of the outfit, J.D Sheldrake (Fred MacMurray), a married man who keeps stringing her along, playing to her vulnerabilities.

We can sense pretty quickly that Baxter and Fran have more in common than they at first realize. Both seem lost in the rat race of corporate New York, and in denial about how their actions undermine their own happiness and self-worth.

Eventually, the smooth-talking Sheldrake hears about Baxter’s apartment, and wants it for himself — and Fran. Now the big promotion comes through for Baxter. He is thrilled until he finally learns who Mr. Sheldrake is taking to his place. Only then is he forced to reckon with his past decisions. Everything comes to a head between Christmas and New Year’s.

The movie holds up beautifully, though feminists and politically-correct types may well cringe at the sexism that pervaded the business world fifty years ago. Witness that over-the-top Christmas party scene, which Wilder actually shot on December 23, 1959. Judged by today's standards, the carousing and all-around naughtiness on display are pretty shocking. (Supposedly, Wilder simply allowed the extras to throw a wild party with plenty of booze, and captured all that transpired on film.)

Also, the randy executives hounding Baxter (Ray Walston, David White, Willard Waterman and David Lewis) are played very broadly (“Premium-wise and billing-wise, we are eighteen percent ahead of last year, October-wise.”). In light of everything else, it is a minor quibble.

Lemmon is superb here, still in the glow of affirmation he experienced doing “Some Like It Hot.” As a result of this — their first of seven collaborations, Wilder was convinced that Jack was a comic genius and more importantly, a truly great actor. This empowered Lemmon to deliver a performance imbued with real pathos. He’s not just playing for laughs here — in this film, we discover for the first time that Jack Lemmon can break our hearts. (He’d do a lot more drama after this, including Blake Edwards’s searing “Days of Wine and Roses” just two years later.)

It’s no surprise that Wilder was always a stickler about adhering to the script. Shirley MacLaine loved to improvise, which drove him crazy. He’d simply force her to re-take scenes. It hardly mattered in the end: over a varied and enduring career, Fran Kubelik remains Shirley’s most winning performance. She is totally beguiling from start to finish.

Still, she was furious when Wilder lifted his improvisation ban for Lemmon in a couple of scenes: watch as Baxter, suffering from flu, unintentionally shoots nose spray right past Sheldrake. Then there’s that indelible moment when Baxter strains spaghetti through a tennis racquet. That was all Jack.

The talented former sportscaster-turned-character actor Paul Douglas (“A Letter to Three Wives,” “Panic in the Streets”) had been Wilder’s first choice to play the loathsome Sheldrake, but right before production began, he died of a heart attack at the age of 52. In a fix, Wilder called his “Double Indemnity” star, Fred MacMurray.

Back in 1944, MacMurray had taken a calculated risk portraying Walter Neff in “Indemnity.” His public expected him to play good guys, so he’d definitely be going against type. Would audiences accept him as a low-life? Thankfully, they did, and the role demonstrated the actor’s versatility. He’d now have access to a broader range of parts, most notably the sniveling, cowardly Lieutenant Tom Keefer in “The Caine Mutiny” (1954).

However, when Wilder came calling again, Fred was cementing a long-term partnership with Walt Disney, with whom he’d make a series of pictures playing genial, affable characters. He’d already completed “The Shaggy Dog” (1959), and was slated for “The Absent-Minded Professor” (1961).

Suddenly, he was being asked to take on the part of J.D Sheldrake, a manipulative liar and adulterer. The same concerns he’d experienced sixteen years before resurfaced, but also the same prevailing instinct: Billy Wilder, perhaps the most gifted director in the business, wanted him. How could he refuse? MacMurray accepted, and would always credit Wilder with challenging him the most as an actor, and getting the best out of him.

(The actor also told the story of a woman who came up to him shortly after the film’s release and hit him with her handbag. It seems she’d taken her young grandson to see it assuming it was a Disney picture.)

“The Apartment” was a monster hit on release, critically and commercially. While the wildly popular “Some Like It Hot” had racked up six Oscar nominations the prior year (including for Wilder and Lemmon), winning just one for Costume Design, “The Apartment” received a whopping ten nods and took home five Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Director, and Original Screenplay. This would turn out to be Wilder’s career peak.

Of course, that’s ancient history now. Over five decades later, what matters is that this touching film still imparts vital wisdom about the importance of personal integrity and the power of true love. These themes are always worthy of our attention, but especially now, as we make our own private resolutions and prepare for the year to come.

More: How "It's a Wonderful Life" Went From Box Office Flop to Christmas Classic