The passing of Mike Nichols yesterday at the age of 83 marks the end of an era in cinema. He was one of the last iconic directors left standing from a golden moment nearly half a century ago when American mainstream movies actually took risks. Most of his paid off.

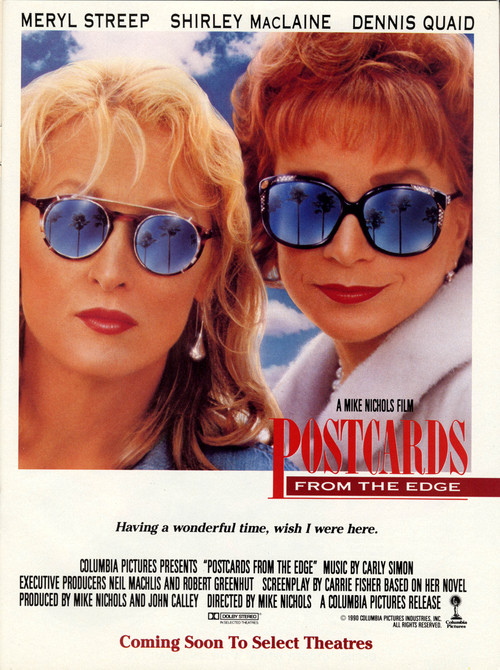

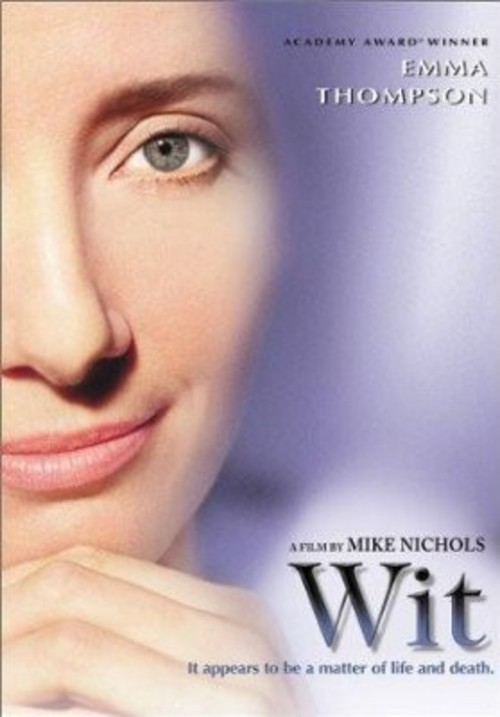

Nichols’s voice was nimble, flexible, by turns comic and tragic, and his range across all of the art forms he mastered, from stand-up comedy, to television, theater, and film, reflected a keen understanding of human foibles and folly. He brought that out in his work with sympathy, subtlety, and a razor-sharp wit.

He started as an actor in the theatre, and first gained notoriety as part of Nichols and May, a comedy team he established with another future director, Elaine May. Heard today, their humor is a very far cry from what passes for stand-up or sketch comedy today- it's dry, intelligent, understated. Positively quaint!

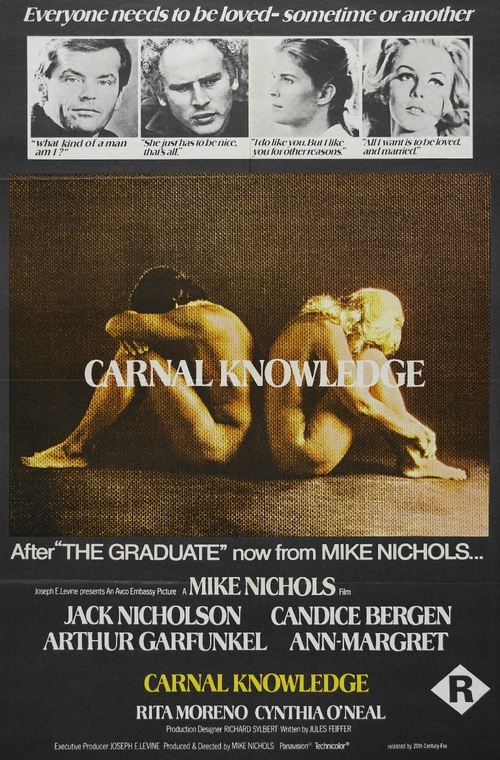

By his mid-thirties, Nichols's explosive, multi-faceted talent led him to film directing and lo and behold, he was a natural. As if making up for lost time, he covered a lot of ground very quickly.

He started off with a bang, first helming “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” (1966), starring Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor, then the two biggest stars in the world. The movie is a blistering verbal game of chess, adapted from Edward Albee’s viciously witty play."Woolf" won two Oscars: Taylor for Best Actress, and a Best Supporting Actress for Sandy Dennis. Nichols was nominated for his direction.

But it was his next movie, “The Graduate” (1967), that managed to capture all the turbulence and angst of the sixties. Dustin Hoffman’s star-making depiction of freshly minted college grad Benjamin Braddock, paralyzed by ambivalence, encapsulated the uncertainty of the time and delivered an anti-hero whose struggle towards selfhood felt universal.

Nichols actually won the best director Oscar this time around. “The Graduate” is still studied in film schools for Nichols’s inventive shooting style and the sheer virtuosity of the film as a whole. Iconic shot: Benjamin smirking nervously in the background, framed in the crook of Mrs. Robinson’s bent knee. (The knee belonged to Anne Bancroft).

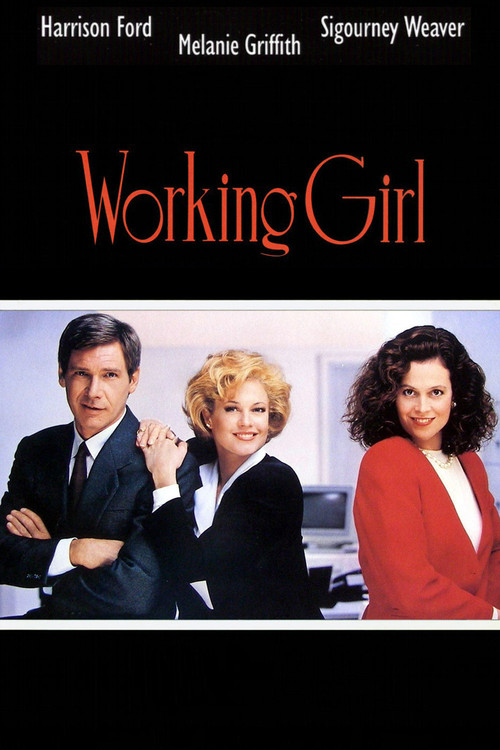

Nichols’s intuitive knack for matching actors and material often defied expectations. “There is no piece of casting in the 20th century that I know of that is more courageous than putting me in that part,” Mr. Hoffman said in an interview in The New Yorker in 2000. Sure enough, Nichols kept making gutsy choices, as when he cast pop singer Cher as a lesbian Oklahoman plutonium processor in “Silkwood” (1983).

Audacious, charming, sly and fiendishly funny, Mike Nichols was the kind of iconoclast that brought to American cinema a deliciously smart, socially relevant edge. We will miss not having him in our midst, not having another Nichols picture to look forward to. Still, his astonishing film legacy remains to inspire new generations of filmmakers and delight younger viewers who have yet to discover his special gift.

Rest in peace, Mike Nichols. And thanks for helping an entire generation avoid a career in plastics.