The first day of shooting in late 1939, a newly minted star named Rosalind Russell showed up on the set of Howard Hawks’s “His Girl Friday” feeling determined, but somewhat on edge. There were reasons beyond the uncertain prospect of starting something new.

Too often in her short film career, she had been second or third choice for a role. As she herself described her early years at MGM, where she’d signed in the mid-thirties: “There was a first wave of top stars, and a second wave to replace them in case they got difficult. I was second in line of defense, behind Myrna Loy.”

Pretty but no bombshell, she’d been mostly relegated to playing proper, well-dressed ladies who served as counterpoint to magnetic A-list stars like Jean Harlow. Worse yet, by this point Roz was almost thirty.

On this particular day, she approached the reserved Hawks knowing she'd been well down the list of candidates to play female reporter Hildy Johnson. Katharine Hepburn, perhaps his favorite female star (they’d done “Bringing Up Baby” the year before) had turned it down. So had most of the other more established comediennes of the day, including Jean Arthur and Carole Lombard (who was too expensive).

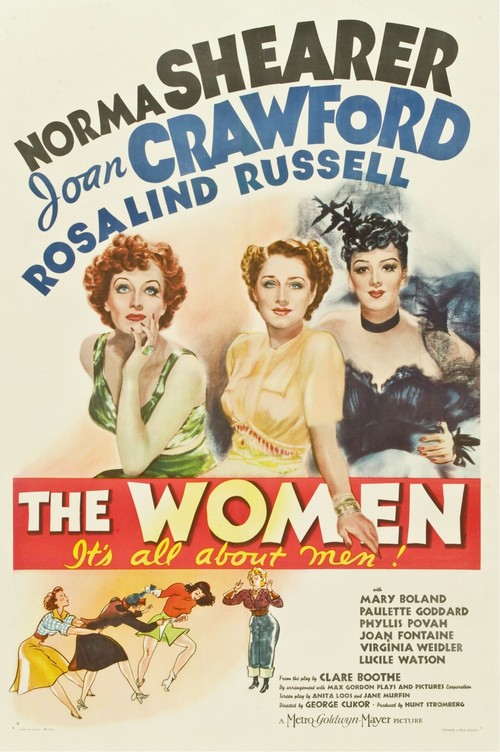

However, Rosalind Russell was used to having to prove herself, both to directors and the studio brass. For years, she’d lobbied for a broader range of parts, yearning in particular to show her comedic chops. In her last picture, 1939's "The Women," she'd finally gotten the chance, playing a catty gossip who stirs up resentments among a group of female friends and rivals. Based on Claire Boothe Luce's hit play and directed by the great George Cukor, it was a prestige picture whose cast included Norma Shearer, Joan Crawford, Paulette Goddard and Joan Fontaine. Still, it was Roz who stole the picture.

But that, of course, was just one film. Could she duplicate her success? Certainly “His Girl Friday” would be a golden opportunity. It was based on the hit play “The Front Page” by Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur which had been first brought to the screen in 1931. The plot concerns a ruthless newspaper editor who schemes to prevent his best reporter from getting married and leaving the paper. Notably, the two main roles in the play and prior movie were for males. (Pat O’Brien and Adolphe Menjou had starred in the first film.)

Nearly ten years later, Hawks, who’d always loved the story, was pondering a remake. He arranged an informal reading where by chance a woman was taking the part of Hildy. It came to him in a flash that the concept could be given a modern twist by making Hildy a female character.

Thus “His Girl Friday” was born. Roz would be working with one of Hollywood’s most admired directors, and perhaps the top male comedy star of the day, Cary Grant. Ralph Bellamy was also on hand in the thankless role of Hildy's fiancé. (Bellamy had also been Grant's comic foil three years earlier in “The Awful Truth.”) In such distinguished company and knowing she was the back-up choice for Hildy, she could be excused for feeling a bit shaky.

Not surprisingly, Roz found it hard to get her footing at the outset. Hawks would watch her and Grant do a scene, and say nothing. She finally got up the nerve to ask the laconic director for his feedback. He looked at her and said: “You just keep pushin’ him around the way you’re doing.”

With this reassurance, she relaxed a bit, although she never felt that Hawks totally respected what she was doing. Still, she sensed she was firing on all cylinders in front of the camera, and so gained the confidence to put an inspired scheme of hers in motion.

In first reading the script, she’d quickly noted that Cary had all the best lines. Hearing that Hawks encouraged improvisation on his films, she secretly hired a writer on her own dime to create lines she could simply insert in a scene.

Another factor made this stratagem easier to pull off. Hawks wanted the dialogue to be super-fast, both to reflect a sense of realism and the urgent, time-sensitive atmosphere of a newsroom. To help achieve this, he directed the actors to actually talk over each other. This became one of the first instances in film of sustained overlapping dialogue.

For a while, no one seemed to notice that Roz was systematically adding unscripted zingers as shooting progressed. However, her co-star, no slouch, was certainly picking up on it. On seeing her first thing in the morning, Cary would often smile at her and say, “What have you got today?” Grant was too much of a pro to complain if he felt that what she was adding to the mix enhanced the movie. And clearly he did.

It didn’t hurt that the two stars got on well. As the two became friendlier, Cary kept bringing up the name of his current houseguest, producer Frederick Brisson. “What’s that, a sandwich?”, Roz responded. It seems Brisson had watched “The Women” several times on a crossing from Europe, and said of Roz’s character, “I’m either going to kill that woman or marry her.” Taking his cue, Cary now wanted to match them up.

Right out of a movie romance, Brisson and Roz met, hit it off, and soon Cary Grant would play one more role: best man at their wedding. Their union would become that all-too-rare thing: a successful Hollywood marriage, lasting right up to Russell’s death from breast cancer in 1976.

“His Girl Friday” opened in early 1940 to generally positive reviews, with some critics faulting its being a remake of a film made less than ten years earlier. Others suggested that Clark Gable would have been better suited than Cary Grant to play duplicitous editor Walter Burns.

These comments have faded into insignificance as the film's reputation has grown over time. Considered today one of our best screwball comedies, it has convulsed generations of viewers and inspired generations of filmmakers.

As to what “His Girl Friday” did for Russell’s career, suffice it to say she’d never again be considered a back-up for anyone. Once and for all, Rosalind Russell had proven herself one of Hollywood's finest actresses.